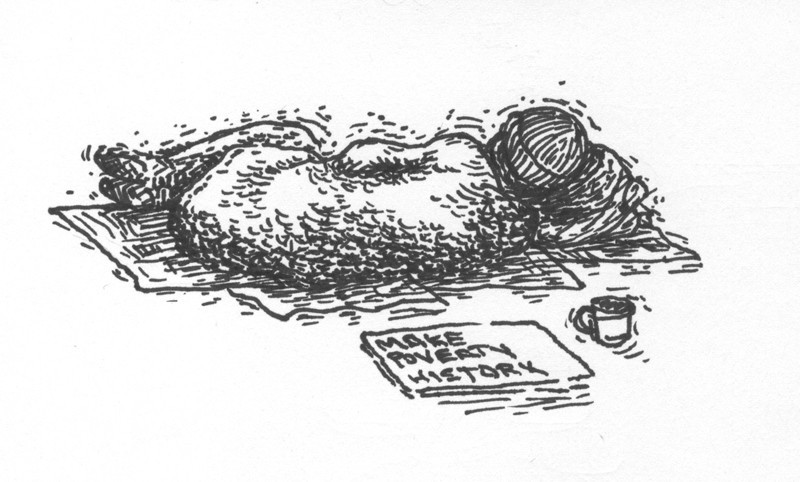

Re-thinking the anti-poverty strategy

Coalitions advocate false dependency

Wading through the ocean of press releases and “calls to action” from Manitoba’s anti-poverty groups in preparation for this piece triggered many feelings. Confusion. Sorrow, perhaps. Exasperation kicked in by the time I had read the term “coalition” for the 400th time.

It is helpful to begin with a cross-section of the groups involved in tackling poverty: The Canadian Federation of Students; the ever-essential Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; Winnipeg Poverty Reduction Council; Dude, Where’s My Poverty; et al.

Yes, there are more, and each group is in a coalition with another group, the coalition of which is again part of yet another coalition. It’s like a three-dimensional Venn diagram from hell: don’t stare directly at it or you’ll go blind from all those “calls to action” layered one on top of each other.

The raison d’être for this assortment of dependency theorists is the view that poverty is a condition thrust upon you by external forces and that sole responsibility for its relief is outside of your own grasp. Lest I be accused of building a straw man, read the material. You won’t get far.

The influences of these groups are playing out currently with the recent influx of African immigrants to Winnipeg’s centre. They arrive poor, yet eager. Typically, parents of these families find relatively low-paying jobs, or they open stores and restaurants in forgotten corners of the city’s core, taking risks that no Asper School of Business student would ever consider. Their labour inspires their children and instils in them desire for a higher education.

“ By labelling public welfare as the “anti-poverty” choice, they prevent the underclass from ever examining real alternatives to the real poverty they experience.

I predict that many of these young kids will be performing advanced medical surgeries on me when I’m 65, while my own daughter by then will still be deciding which of her many partial bachelor’s degrees to finish.

Unless, that is, instead of re-inforcing the idea that poverty is overcome by concepts such as specialization, wage labour and economies of scale, these new Canadians are handed a megaphone as soon as they arrive in Winnipeg and told where to stand and yell.

When I read a poster in the West End decrying the notion that 32 per cent of new immigrants to Manitoba live below the poverty line, I was actually not sure what to do with that statistic.

Are we to imagine that a family from sub-Saharan Africa decides one day that instead of living under a kleptocracy, they have just simply had enough and inform their family that they’re going to move to Wolesley? “We’re thinking maybe Palmerston Avenue, I heard there’s an organic bakery close by and that you simply HAVE to try the cinnamon buns.”

This is where the sorrow kicks in. By labelling public welfare as the “anti-poverty” choice, they prevent the underclass from ever examining real alternatives to the real poverty they experience. The “anti-poverty” label also stifles public debate and does seem a little condescending: Let me figure this out, if you’re not anti-poverty, you must be ... Gasp!

My father worked at the bottom of a coal mine in rural Zimbabwe when he was young, the same way his father worked at the bottom of that same mine. One day my dad decided to leave the mine. Against all odds, he became a doctor and later moved our family from Africa to rural Manitoba. Because of this, I now have the fortune of living in a country where a wheelbarrow full of money buys you more than a loaf of bread.

I’m just glad that the day he left the coal mine there wasn’t an anti-poverty coalition waiting at the top of the mine shaft telling him that the best way improve his fortunes was to lobby the state.

Gareth du Plooy is a first-year science student at the University of Winnipeg.

Published in Volume 64, Number 9 of The Uniter (October 29, 2009)