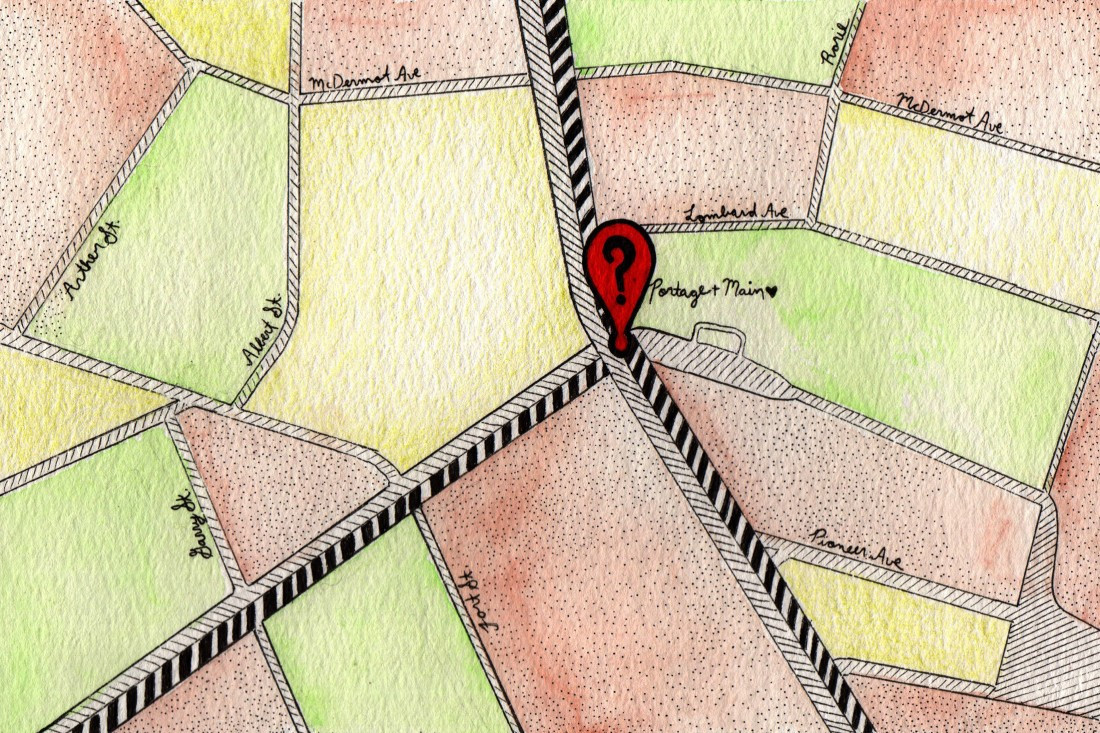

Portage and Maybe…

The famous intersection remains a symbol of the city’s decision-making ineptitude

One of Brian Bowman’s promises as he became the new mayor of Winnipeg was to open up the city’s most famous intersection to pedestrians.

Portage and Main was closed 37 years ago, when a modernization strategy of the city was to separate cars and pedestrians, presumably to increase efficient vehicle flow through the intersection.

Since the mayor’s inauguration, the topic has come up in the press several times, and commenters have mixed reviews.

It has now reared its head again with the closing of the 2016 Winnipeg Design Festival. The final event was held on the plaza at the Richardson Building and included a panel discussion with some of the city’s well-known designers and advocates.

The general argument the panelists made was adding a pedestrian crossing would create opportunities for new businesses and add a human dimension to the otherwise car-centred space.

The main problem with Portage and Main, however, is not in the decision whether to open the intersection above ground – it is that the argument remains stagnant.

In a poll done by the CAA in August, many citizens said they fear traffic congestion and pedestrian safety were the intersection to open. These could be legitimate concerns, but it is difficult to know for sure, because the public has not seen any traffic assessments, safety assessments or feasibility studies, all of which are viable.

Urban consultants – people who spec-ialize in land management, economic development and transportation, among other things – could be hired to perform these assessments. Their findings would be reviewed and presented, along with case studies, to those in city council who are in positions to create real change. This decision-making process could then be made public.

Currently, it is difficult to find any information on what urban experts really think of the issue, and therefore easier for the population to fall back on their assumptions of what could happen if the intersection were to open.

Although the organizers of the Design Festival and other design events such as the River City 2050 discussion (held at the Free Press Cafe in February) are well-intentioned, the events tend to not reach an audience beyond design professionals, academics and students. These events therefore do not raise awareness to other members of the citizenry who are not already engaged and interested in the topic.

Portage and Main has the potential to become a positive example for our city, but right now it is a symbol of the problem with innovation in our city: designers and thinkers have no way of transmitting their ideas to decision-makers, because they continue to preach to the choir, and policy-makers seem to have no process set in place for adopting new ideas into realistic propositions.

This is an issue when small decisions, like the pedestrian access of an iconic intersection, create precedents and gather momentum for other more important changes that need to be made within the city.

Kyla Crawford is a graduate of the Environmental Design program at the University of Manitoba and a self-proclaimed urban advocate.

Published in Volume 71, Number 4 of The Uniter (September 29, 2016)