One way out

Veganism can help solve the world’s mounting problems

Vegans - those who do not consume any animal products - are too often dismissed as health nuts or animal rights fanatics.

While veganism certainly has its health benefits, and is undeniably a more compassionate, animal-friendly lifestyle, the positive effects of a vegan diet in terms of the environment and world hunger are profound and should be highlighted, particularly given the context of our planet’s population recently reaching the seven billion benchmark.

The health and animal rights arguments for veganism are not convincing to many, but those who choose an omnivorous, as opposed to plant-based, diet should be aware of the significant consequences of their consumption habits relating to their fellow human beings.

It is not only fringe activist groups advocating a global shift toward a vegan diet.

In 2010, a United Nations Environment Programme report stated that “impacts from agriculture are expected to increase substantially due to population growth increasing consumption of animal products. Unlike fossil fuels, it is difficult to look for alternatives: people have to eat. A substantial reduction of impacts would only be possible with a substantial worldwide diet change, away from animal products.”

In 2011, the United Nations stated that their previous population growth estimates had in fact been too low, and that instead of capping off at nine billion in 2050, the world population is likely to keep growing to 10 billion by the year 2100.

Worldwide meat consumption is estimated to double by 2050, and total global food production will have to increase by 70 per cent to meet the demands of a population of nine billion.

The recent trend toward buying locally sourced foods as a means of curbing one’s environmental impact has been shown to be entirely inferior to switching to a plant-based diet for even one day a week.

A 2011 study in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology stated that “‘buying local’ could achieve, at maximum, around a four to five per cent reduction in GHG emissions due to large sources of both CO2 and non-CO2 emissions in the production of food. Shifting less than one day per week’s (i.e., one seventh of total calories) consumption of red meat and/or dairy to other protein sources or a vegetable-based diet could have the same climate impact as buying all household food from local providers.”

That is why Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, chair of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, is urging a global campaign to encourage people to adopt a meat-free diet one day per week.

If the effects of one meat-free day per week are so profound, imagine the effects of a complete universal shift to a meat-free diet.

How exactly is animal agriculture damaging the environment?

The livestock industry produces 18 per cent of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions, or 51 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity.

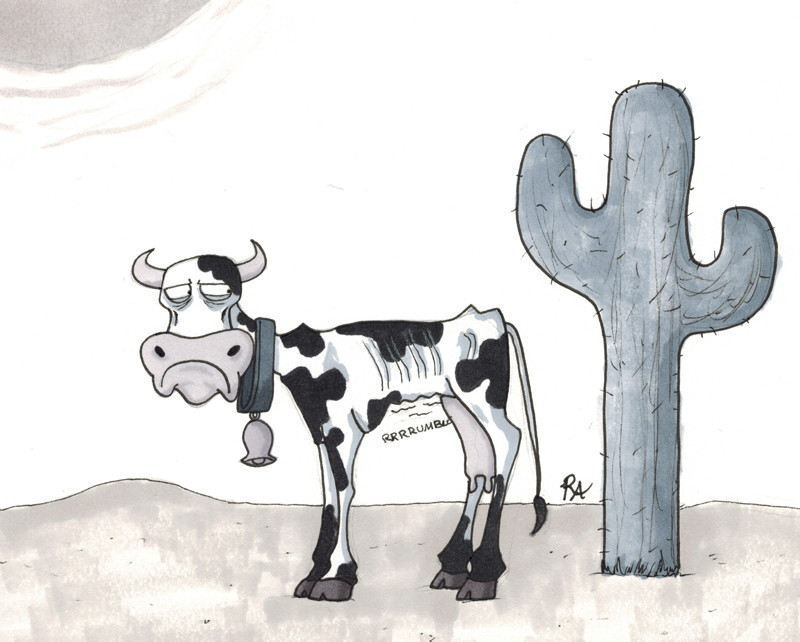

Methane, the gas produced by cows, sheep and other ruminant livestock, is a greenhouse gas 25 per cent more potent that carbon dioxide.

A 2011 Environmental Working Group study found that if everyone in the United States switched to a diet free of meat and cheese just one day a week for one year, it would be the equivalent of taking 7.6 million cars off the road.

Similarly, a 2012 Lancaster University study found that if everyone in Britain switched to a plant-based diet, it would be the environmental equivalent of taking half of all Britain’s cars off the road.

It is not merely greenhouse gas emissions that make animal agriculture unsustainable.

Agriculture, particularly meat and dairy production, accounts for 70 per cent of global freshwater consumption and 38 per cent of total land use.

Feed production, waste, pesticides, fertilizer, fuel, processing and transportation are all additional contributing factors.

Consider these numbers: it takes 16 pounds of grain to produce one pound of animal flesh.

According to the United Nations, one acre of land used to raise cattle yields 20 grams of protein while the same acre would yield 17 times that amount if it were used to grow soybeans instead.

It takes 4,000 gallons of water per day to produce food for a meat-eater but only 300 gallons for a vegan. Therefore, food for a vegan can be produced on one sixth of an acre of land, while food for a meat eater requires three quarters of an acre.

If all the arable land on the planet were equally divided between humans, every person would get two thirds of an acre, which is plenty for a vegan but insufficient for an omnivore. It must be asked why we are wasting so many precious water, grain and land resources on raising livestock when there are 840 million people on the planet going hungry ever day.

The issue isn’t that there isn’t enough food to go around. The issue is that the more meat we consume, the fewer people we are capable of feeding.

It was a deliberate choice to make the content of this article primarily statistical. This is because when arguing on behalf of veganism from a moral standpoint, one is often met with ridicule or hostility.

Hopefully these facts speak for themselves, and if readers are not convinced by the benevolent animal rights argument, perhaps they will consider reassessing their diet for the sake of humanity and our future on this planet.

Katerina Tefft is a politics student at the University of Winnipeg.

Next week in The Uniter: “Three reasons why I am a vegan” by Comeback Kid co-founder and guitarist Jeremy Hiebert.

Published in Volume 66, Number 21 of The Uniter (March 1, 2012)