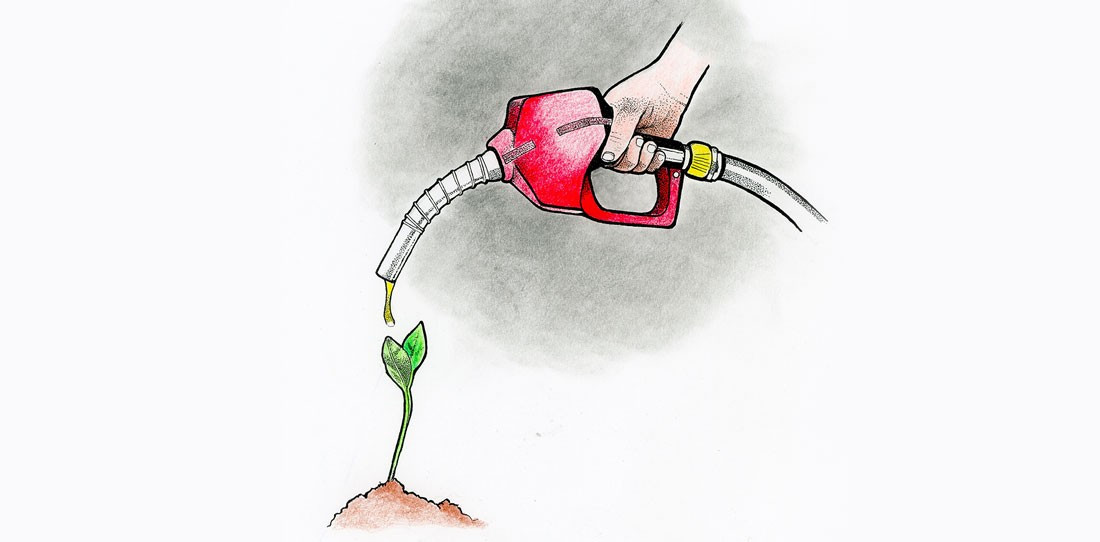

Oil double-check

Evaluating Manitoba’s proposed increase in biofuel content requirements

On Jan. 21, Premier Brian Pallister announced that the Made-In-Manitoba Climate and Green Plan would include the highest ethanol content requirement and highest biodiesel requirement of any province in Canada. The plan is “built on the strategic pillars of climate, jobs, water, and nature,” and purports to make Manitoba the cleanest and greenest province while advancing its economy and infrastructure.

David Herbert, a synthetic chemist (a chemist working to create complex chemical bonds and reactions for a specific purpose) who focuses on molecular design for sustainable energy applications, says that when he heard about the new standards, he “thought they were fine.”

“Manitoba, as a province, we contribute a small amount of Canada’s overall emissions ... but with respect to Ontario or Quebec, who, compared to 1990 levels, have lowered their emissions as of 2017, Manitoba’s emissions are low but are moving in the wrong direction,” he says.

Alberta, which has the highest provincial emission rate in Canada, jumped from around 170 megatons of carbon dioxide to 270 between 1990 and 2017, while Manitoba moved from 18 to around 25.

“Changes to fuel standards can impact the carbon intensity of fuels used in the transportation sector,” Herbert says. “It doesn’t seek to or propose to lower the overall consumption of fuels, which plays a big factor in the overall emissions from that sector.”

Herbert says relative to the Canada Clean Fuel Standards, which do not prioritize a specific additive or mechanism to reduce the carbon intensity of gasoline and diesel fuels, the emphasis on biofuel and announcement of the new provincial fuel standards at Manitoba Ag Days, held annually in January in Brandon, does imply a quite specific vision of a greener Manitoba.

“The tie-in is kind of obvious. It seems that the renewable content is supposed to come from agricultural feedstock,” he says.

“Biodiesel trade associations are sometimes feedstock-neutral in that they don’t try to pick a winner, but it looks like these fuel standards are trying to do two things: one is tackle overall emissions from carbon-intensive fuels that are used for transportation, and two is to promote (the) local provincial sector - agriculture - for fuel purposes, so that has its own benefits and drawbacks,” he says.

This is why Curtis Hull, project director for Climate Change Connection (a charitable non-government organization working to educate Manitobans about climate change) is hesitant about the new standard.

“We need to be cautious about increasing the use of biofuels, because the greenhouse gas emission reduction from biofuels can be pretty tricky to measure,” he says, because the emissions of the production and transportation need to be taken into consideration, as well as whether crops for fuel are using land that could be used for growing food.

Hull also says there needs to be “effort made as soon as possible to move us towards electrification” to meet climate goals. He favours the Corporate Average Fuel Economy approach, which could be applied to incentivize automobile manufacturers to increase the production of electric vehicles relative to combustion-engine vehicles.

Herbert says the push for biofuels may incentivize shifts in research interest in and implementation of alternatives to gasoline and diesel, and that transportation companies already working on electrification are left out, but that “changing fuel standards are absolutely necessary; despite the growing prevalence of electric cars. We’re just not there yet.”

Published in Volume 74, Number 17 of The Uniter (February 6, 2020)