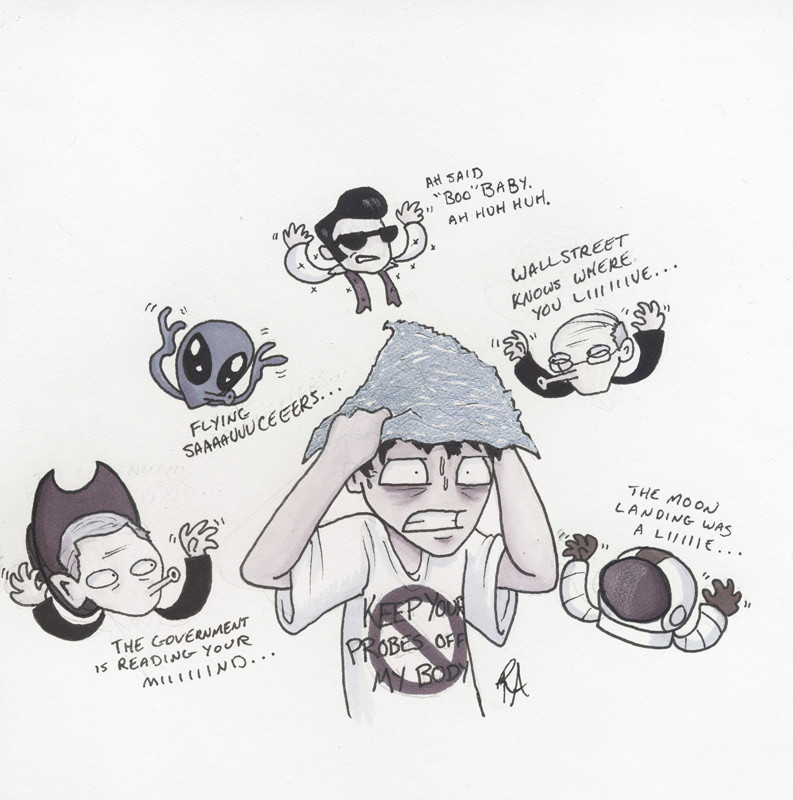

It’s not true!

Conspiracy theories have evolved, but still challenge our knowledge

The conspiracy theorists of old talked about aliens and JFK, the pressing issues of the time. But today’s conspiracy theorists have branched out and expanded their knowledge base, taking on diverse issues from theoretical physics to fast food.

The motivation for the theories is essentially the same as the old days, but I think there are some notable differences between conspiracy theorists then and now.

First off, the range of conspiracy theories that have become popular knowledge is so wide that many of us, strictly speaking, may be called conspiracy theorists.

Bear in mind that in the old days, you either thought aliens were nonsense, or you hid naked on the side of the highway in hope that the mother ship would descend upon you.

Now there’s an extensive middle ground between these two extremes.

But this middle ground - the people who don’t necessarily believe heavily in every subversive idea, but who nonetheless are curious - is certainly not who I’m talking about.

I’m talking about those people who can explain the systems of the world for you in five minutes, simply by summarizing Zeitgeist.

They will refute your every rebuttal, or at least ignore it.

This is the thing about today’s conspiracy theorists: they’ve watched films that explain the world in its entirety, and so feel that nothing else matters.

I think believing in this stuff promotes a depressing existence. How can you dive into life meaningfully when you believe that everything you or anyone feels is the product of a mass system that has

programmed our every emotion?

When it comes to the arts, these theories are also damaging, and sometimes make arguments that are irrelevant anyway.

A great example of this is the recent movie about the works of Shakespeare, Anonymous, which appears to treat a theory from the 19th century as if it’s something new.

In fact, the film promotes one of the many theories surrounding the authorship of the Shakespearean plays, but the story is always either that there was no William Shakespeare, or that if there was he was only an actor and not a writer of plays.

My point is that I don’t see why this matters. Literary theory has long since moved away from studying the author anyway, and the focus has turned to the work itself.

Hardcore conspiracy theorists have reduced the great works of the ages to products of mind control, and thereby created a means with which to disengage from the works themselves. That’s why some people don’t read anything but alternative news sources.

You may call me naïve, but I believe there has been human achievement.

In fact, I believe that part of the force that drives these conspiracy theories is the extreme to which our achievements have gone.

Throughout the history of humankind, back to the ancient Greeks at least, people have dreamed of flight - a goal we achieved about a century ago.

Our ancient ancestors dreamed of flying, but they could never have imagined the Internet, or smartphones.

In this sense, humankind in the Western world is in its post-classical era, detached from what came before it. Magic has happened, genius has changed the world - and now what?

We move incrementally along the same path: phones that are slightly better, Internet that’s slightly faster.

But nothing truly inspiring abounds. This generational hopelessness is at the core of many conspiracy theorists’ motivation, I believe.

That may be their focus, but for the rest of us life goes on in the matrix, and we are blissfully unaware.

Trevor Graumann is the The Uniter’s comments editor.

Published in Volume 66, Number 13 of The Uniter (November 23, 2011)