Homicide rate dropping but still high

Manitoba’s homicide rate a social issue, not a criminal issue

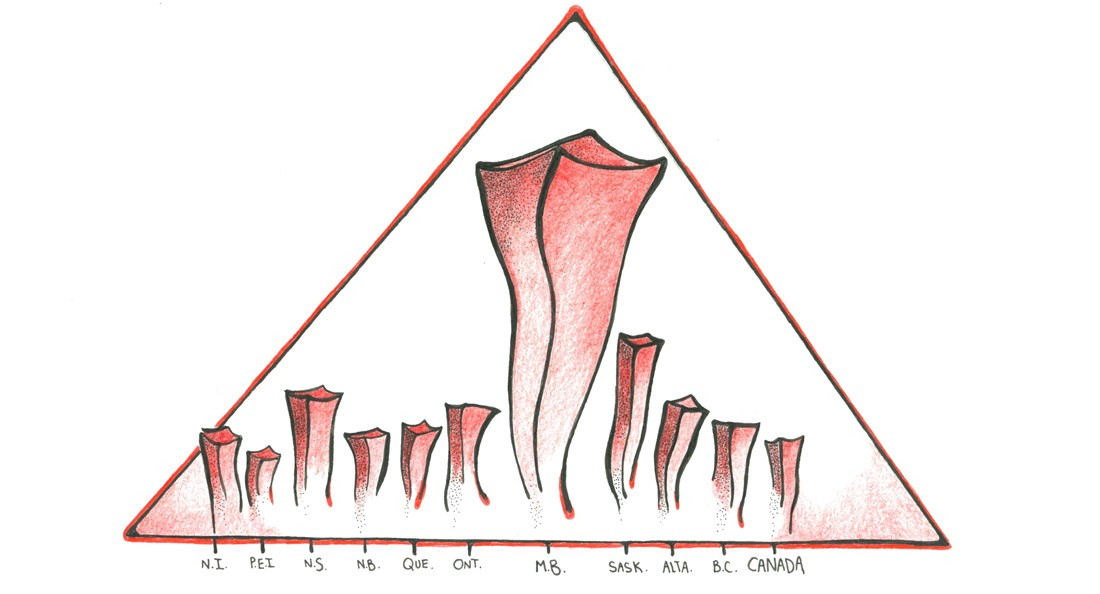

In Manitoba, homicide rates have fallen but are still some of the highest in the country. 2016 saw Manitoba’s homicide rate fall from an average of 3.63 to 3.19 people per 100,000, second only to Saskatchewan’s, which was 4.69.

Homicide rates are calculated by taking the number of homicides reported in a year in a given area, dividing by the population of said area, and then multiplying by 100,000 in order to yield a rate of homicides per 100,000 people.

Steven Kohm, chair of the Criminal Justice Department at the University of Winnipeg (U of W), notes that this method can be misleading in some situations.

“Because it’s a ratio, the homicide rate is very sensitive to small populations. For instance, homicide rates are often very high in the northern territories, because it only takes a few homicides to drive up rates per population,” he says.

In 2016, there were 42 homicides in Manitoba, 54 in Saskatchewan and 206 in Ontario.

Due to the reliability and consistency of the reporting of homicides, the homicide rate has long been used as an indicator of the level of violence in a society. This is the case because other violent crimes, such as assault and robbery, are not always reliably or consistently reported to police departments.

For some, these numbers confirm their feelings of insecurity about living in Manitoba. Alissa Haley, a fourth-year student at the U of W, who is originally from Ontario, says that she is not surprised that Manitoba has some of the highest homicide rates in the country.

“There’s still a great community here, but at the same time … personally, I’m scared to walk alone myself, just ’cause I’m not from the area especially,” she says. “Obviously, anytime I walk anywhere, running (through) my head I’m like, ‘I could get murdered.’ I know that’s horrible, but (it’s a) reality.”

Although Haley says she feels this way, she also admits that in the six years she’s been living here, she hasn’t had any issues.

Some criminologists believe that this perception of imminent violent crime is partly fuelled by the media.

Scot Wartley is an associate professor of criminology at the University of Toronto (U of T). In 2011, in a Q&A with the Research and Innovation department of the U of T, he stated that “compared to 20 or 30 years ago, coverage of crime is a much larger proportion of all news coverage … we receive much more sensationalistic coverage. We receive the gory details.”

In 2016, homicides accounted for less than 0.2 per cent of violent crimes reported by police across Canada.

“Frankly, there’s other things I would worry about more than the homicide rate. It’s one indicator. It’s something that people like to focus on and obsess about, but I would look at what’s happening to crime more generally,” Kohm says.

For Kohm, the homicide rate is an expression of social breakdowns within the justice system.

“It’s a social issue. This is the thing, there’s an old saying, ‘if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.’ We’re viewing (the homicide rate) as if there was a criminal justice response here,” he says.

He adds that the contributing factors in homicide cases need to be examined and addressed.

“I think if we address things like domestic violence, alcohol and drug abuse, addiction, broken families, legacies of the child welfare system and residential schools, all those sorts of things are contributing, and those are really beyond the reach of the justice system.”

Published in Volume 72, Number 14 of The Uniter (January 18, 2018)