Gritty City documents early Winnipeg hip-hop scene

‘It’s never just been about the music’

In December 2019, former

In December 2019, former Stylus Magazine hip-hop writer Nigel Webber dug into researching his passion project, Gritty City: An Oral History of Winnipeg Hip-Hop Music 1980 to 2005, not knowing that the world was about to shut down.

Stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, Webber profited from the extra time.

“I just started hopping on the phone with people,” he says.

From there began a three-year process of interviewing and transcribing more than 180 conversations with some of Winnipeg’s most legendary hip-hop artists spanning the first 25 years of its history. He plans to release a sequel that picks up in 2005 to the present day.

Self-published through FriesenPress Publishing, the book is in its final approval phase and is set to launch in June 2024. Between the covers are firsthand accounts from the many artists who brought hip-hop to Winnipeg. Webber’s goal is to document this generation’s significant contributions before their stories are lost forever.

“A majority of the book is told through the voices of the people who actually lived the history,” book consultant and Winnipeg hip-hop artist Elliott Walsh, aka Nestor Wynrush, says.

Walsh gave Webber, who is not a hip-hop artist himself, a credible reference and introduced him to many of the artists, activists, producers and promoters who grandparented the Winnipeg hip-hop scene – including the late Gerry Atwell, DJ Bunny and DJ Alibaba.

“You want someone that takes what you’re doing seriously or what you have done seriously,” Walsh says, adding that the artists felt respected and heard by Webber.

Recognizing that these are predominantly BIPOC narratives, it was important for Webber to take a backseat to their perspectives.

“Not only is this documenting stories of ... predominantly Black, Brown, Indigenous people – (it is) documenting them before it’s too late and treating them with respect,” Webber says.

“It’s never just been about the music,” Walsh says. “It is our migration patterns and the racism in the city and battles for equity.”

Webber says he wants to avoid passing hip-hop off as a subgenre in the larger his- tory of Winnipeg or Canadian music and to treat the artists as individual contributors.

“I think it deserves to have its own history and be recognized as a really important cultural art form,” he says.

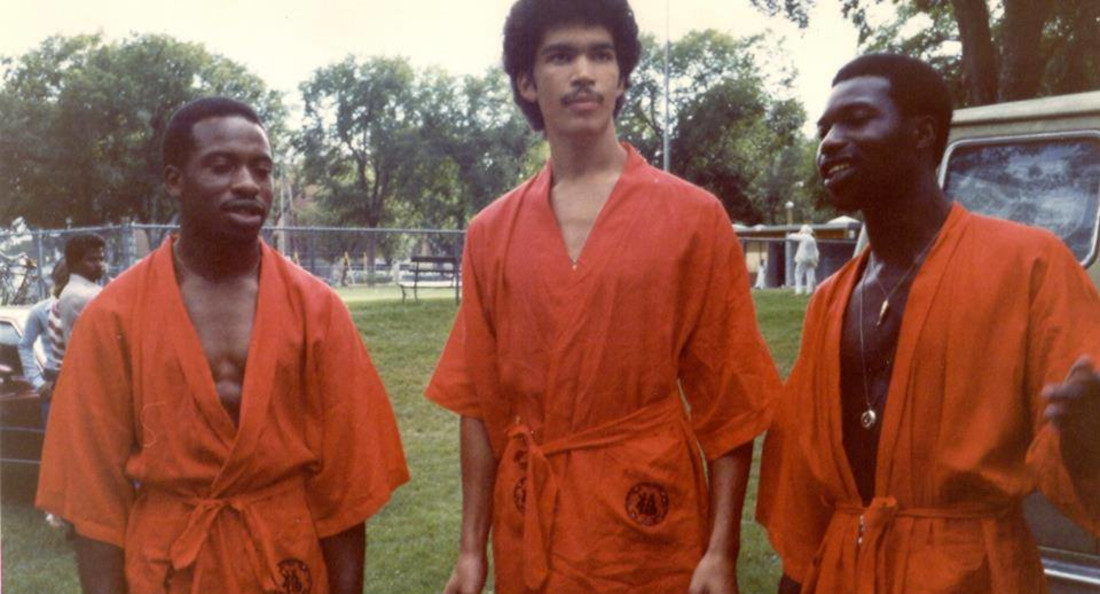

Hip-hop came to Winnipeg through many channels, Walsh says, including immigration from the Caribbean, the Black- O-Rama Reggae Festival, MuchMusic’s RapCity, Spotlight (VPW), radio (NCI) and tapes being shared from relatives in American cities.

“It looked like rebel music. It was a reaction, and there’s a reason why this music has survived and why it spread, why it even made sense to young Indigenous folks at the time,” Walsh says.

Webber and Walsh both consider the book a Winnipeg history that addresses how the genre responds to the “gritty” histories of racism, class divisions and oppression that inform the city’s culture as a whole.

“If you’re not a hip-hop fan and not even from Winnipeg, (you can) still come away with some form of appreciation, I hope,” Webber says.

“It’s a history of the people of the city of Winnipeg. It’s conversations that aren’t always had out in the open,” Walsh says. “And, hopefully, they will cause more conversations.”

Published in Volume 78, Number 20 of The Uniter (March 7, 2024)