A burial ‘good enough for Jesus’

One green city

Death is an uncomfortable topic, especially since everyone’s inevitable demise could harm the planet. It seems people can’t even die without adding to their carbon footprints.

For every person cremated, approximately 400 kg of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, which is the equivalent of driving a car about 800 km.

Around 75 per cent of Canadians choose to be cremated, and 11,000 Manitobans die each year, which means this province alone releases 330,000 kg of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every 12 months.

Those seeking a classic tombstone and coffin burial aren’t off the hook environmentally, either. Embalming fluids eventually leach out of caskets and into the earth and can reach water systems.

Plus, although their residents likely don’t care or notice, cemeteries use a significant amount of water, fertilizer and pesticides to keep their grass green.

Green burials are a more environmentally friendly choice for a person’s body after death.

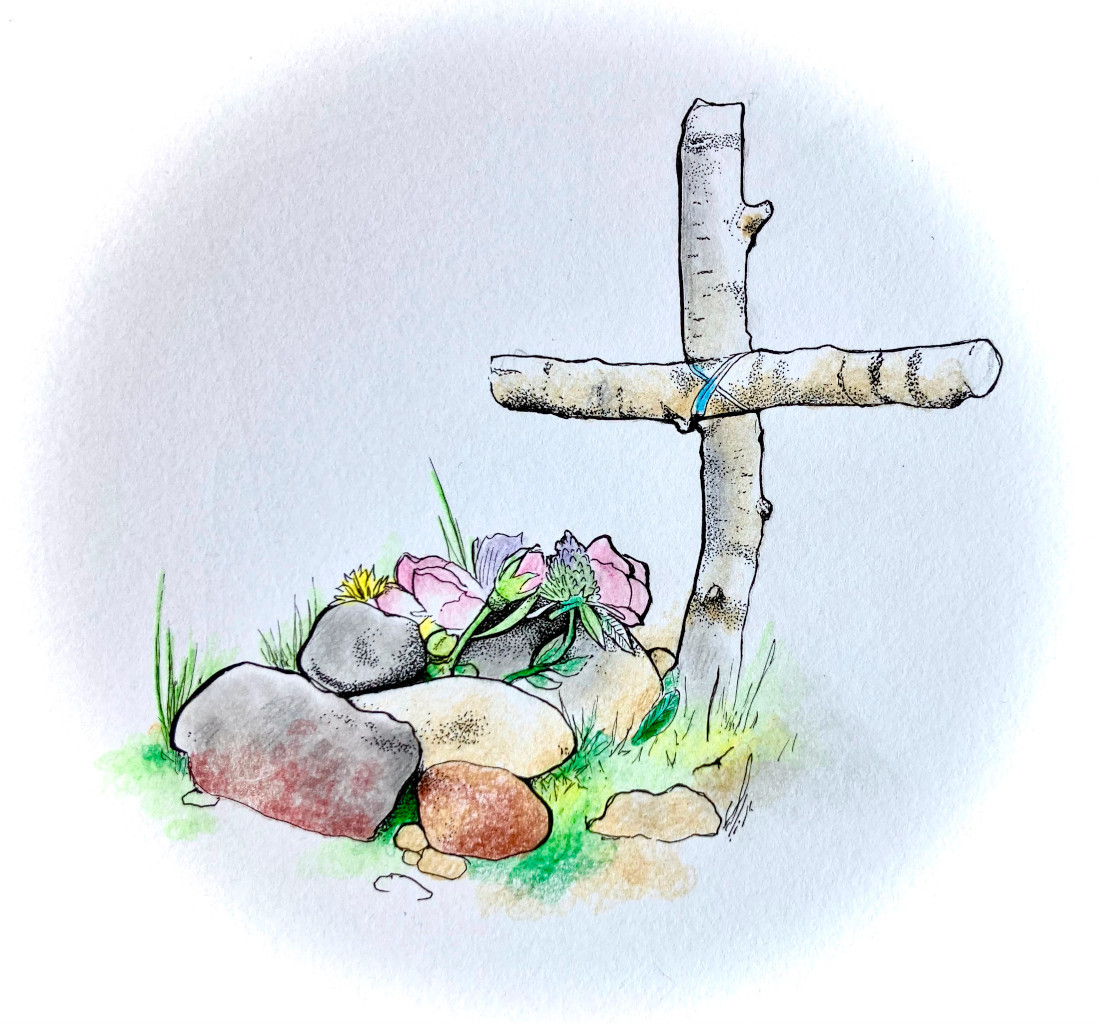

In a green burial, a body is not embalmed. Instead, it’s wrapped in a cotton shroud, sometimes in a biodegradable casket, and placed into the earth. Friends and family members may also plant trees or flowers over the spot to memorialize their loved one.

No carbon dioxide is added to the atmosphere, and no toxic chemicals are added to the ground. This way, the earth takes care of the dead, just how it always has.

Not only is a green burial better for the planet, but it also saves a grieving family money. A complete green burial costs as much as the average casket, somewhere between $2,000 and $5,000.

As of 2021, there are only 12 cemeteries devoted to green burials in Canada, none of which are in Winnipeg. There are spaces in St. Vital, Brookside and Transcona that offer plots for green burials within traditional cemeteries.

Richard Rosin, a funeral director with more than 40 years of experience, not only predicts Winnipeg will have a cemetery devoted to green burials in the next five years but pictures them as ecological learning centres.

“You develop it into an environmentally friendly place, not just a cemetery. Maybe it’s a place kids can watch pollinators in the spring. It becomes a place about life and learning, not only death,” he says.

He says there is very little distinction between a traditional burial and a green burial. The only difference is that the latter involves bodies buried within the first five feet of soil, where there is more oxygen flow and bacteria.

He’s noticed the city has been looking into green burials and earmarked a few spots for potential sites. However, the idea of returning to the earth might not appeal to everyone.

It might simply take getting used to the idea. A green burial isn’t really any stranger than being artificially preserved in an expensive box or being turned into ash – but it’s better for the planet.

For environmentalists, it could help to know they were dedicated to the cause until the very end.

“People are thinking of their legacy. They’ve been composting, changing lightbulbs and maybe lobbying for the environment while they were alive. Now they’re thinking ‘what do I do at the end of it all?’” Rosin says.

He plans to have a green burial when it’s time for his own funeral.

“You know, just a shroud was good enough for Jesus,” Rosin says.

Allyn Lyons is a graduate of the University of Winnipeg and Red River College’s Creative Communications joint-degree program. It’s pronounced uh-lyn.

Published in Volume 77, Number 07 of The Uniter (October 27, 2022)