Working in the aftermath

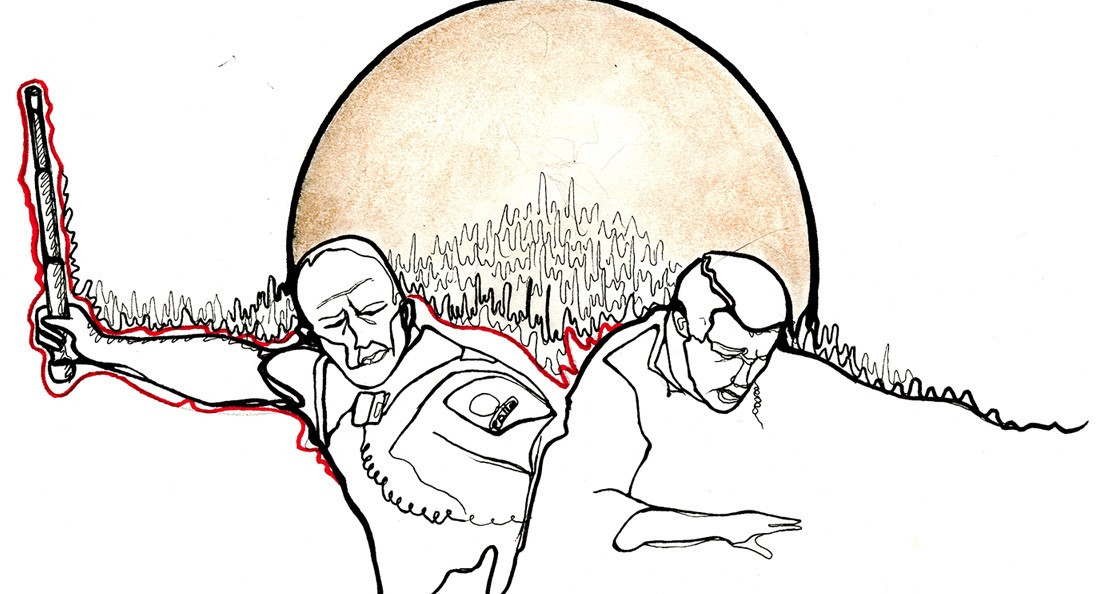

Four people have been killed by Winnipeg police this year. This is what happens afterward.

There are very few official options for the families and communities of people shot by the police. While those who knew the deceased may seek justice through official channels, there is a lot of work that often happens outside of governmental bureaucracies: organizing, supporting families of the victim and countering pro-police rhetoric.

When Sandy Deng, a member of the Council of South Sudanese Communities of Manitoba (COSSCOM), heard about the shooting of Machuar Madut on Feb. 23, she was with members of Winnipeg’s South Sudanese community at the home of the President of the Council, Martino Laku, whose mother had just passed away.

“Everyone went into a shock. It was just one of these things where we didn’t expect him to be the one this sort of thing would happen to,” Deng says.

The Law Enforcement Review Agency (LERA) oversees conduct complaints about police officers, which does include police brutality, and the Independent Investigations Unit of Manitoba (IIUM) investigates criminal complaints against the force. LERA is the only public-facing organization of the two.

Duane Rohne, the commissioner for LERA, says figuring out whether an incident would be better investigated as a criminal or conduct complaint is “not an easy decision to arrive at,” because those filing the complaint often are not super familiar with the system.

He says LERA is always willing to find a time to help people figure out what course of action they would like to take.

If a person wishes to file a criminal complaint, they have to go through the police department, and if the department decides their complaint is worthy of investigation, they pass it on to the IIUM. Members of the public cannot access the IIUM directly.

The friends and families of victims of people killed by police often have difficulty getting real justice, and though they may eventually take the police department to court, in the immediate aftermath of tragedy, it is their communities, and not the government, that often steps in.

Deng says the first thing the South Sudanese community thought to do was rally. She says they began organizing the very next day.

The day after the news broke, other community members sent out a press release and condemned the actions of the Winnipeg Police Service. The same day, the police issued their statement on the shooting, which mentioned they were responding to a break-and-enter.

“We were very infuriated that they said this,” Deng says.

“Some of the members were saying that we shouldn’t do the rally right away, because we need to wait for the police and what they’re going to say, and my response was that they’re not going to say anything positive, so it doesn’t matter how long they wait,” she says.

”When they came up with that story that they concocted, it was just a devastating blow to the community, because at least we thought they were going to say something else,” she says. “When it’s his own apartment that he was killed in … It doesn’t make any sense. It doesn’t add up, what they said to the media.”

Members of the South Sudanese community held the rally six days after Madut was killed.

“A lot of the leaders of the South Sudanese community in Winnipeg were there, and everybody had their piece on what, unanimously we knew, what was done, which was not right,” she says.

“(We) condemned the actions of the police of using deadly force on someone that’s been struggling with mental health issues and has a language barrier and just being in this country trying to adjust, and on top of it, the whole scenario about the call being an attempted break-and-enter with a hammer,”

she says.

Deng organized a GoFundMe to pay for the travel costs of Madut’s family in attending his funeral and to raise funds for Madut’s family to seek justice for the killing and an apology for the police’s slanderous characterization of Madut in the press release.

She says the community has received support and solidarity from several Indigenous leaders, Black Space Winnipeg and a local lawyer.

She says she hopes to see solidarity from more marginalized communities in the city, and that white Winnipeggers need to use their privilege to help marginalized people and to provide financial and emotional support to grieving communities if they are able.

Deng says people need to understand that the victims of police brutality often are not criminals and that racial profiling by the police has a profound effect on marginalized people’s ability to

feel safe.

“That’s something people need to be sensitive to and be aware of, and know that we’re not making a big deal out of nothing,” she says.

Both Deng, and John Williams, who runs the Facebook group “enough is enough from police brutality here in Winnipeg against indigenous” (enough is enough) say that while marginalized, especially racialized people, in Winnipeg are very aware of the police department’s problem with unaddressed lethal brutality, privileged and white people and mainstream media groups have failed to grasp the extent of the issue.

Williams, who is white, says that while “enough is enough” says that while “there are really good hearts in Winnipeg,” in his experience, “you gotta do things on your own. That’s how people treat you.”

Williams’ son, Chad Williams, who is Indigenous, was killed by police on Jan. 11, 2019.

He says the police misrepresented the circumstances of Chad’s death and mischaracterized Chad as a criminal when he was actually co-operative and fully aware of his rights.

“We were all there when this happened,” Williams says.

Williams says the local Indigenous community has been supportive of his family in this tragedy, but that white people have failed to provide support in the same way.

“People do not understand what it is to be below the poverty line,” he says.

Williams also says he has witnessed contempt and ridicule from police at past rallies.

He says that “enough is enough” is a group where people “calm each other down,” so that they can focus their energy on organizing against police violence.

He says they plan to hold a rally when the weather warms up.

“We have plans to go down to the police centre and shake that building” and confront Manitoba’s justice minister, he says.

Published in Volume 73, Number 22 of The Uniter (March 21, 2019)