Winnipeg as we know it

Examining the decisions that have made Winnipeg what it is today

Download this two page feature with photos or read the text version below.

Winnipeggers love to talk about what needs to be fixed in our city. Most people realize that we need more residential housing in our downtown, that our transit system requires a serious overhaul, and that our continuous outward expansion is only hurting us – from the infrastructure we can’t afford to keep up, to the car-dependent, unsustainable lifestyles that suburban living necessitates.

In the same breath, not everything in our city requires a complete overhaul. Our city has some great characteristics that should be celebrated – from the The Forks and Waterfront drive to the slow revitalization of the Exchange District.

In order to plan for the future, we have to understand our past. What are some of the decisions that shaped our city as we know it? In honour of The Uniter’s Urban Issue, we spoke with some of Winnipeg’s most knowledgeable, including Robert Galston, author of local blog The Rise and Sprawl, about the decisions that have affected Winnipeg as we know it.

Plopping down the Centennial and Civic centres

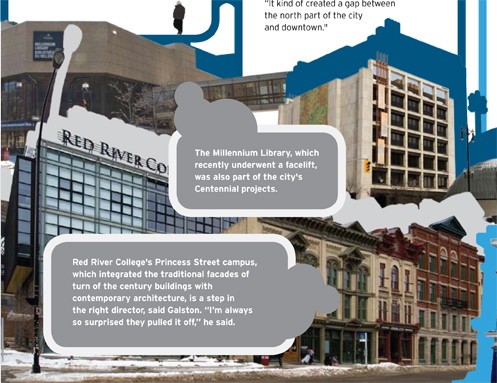

The raw concrete, or Brutalist-style architecture, that characterizes our Centennial and Civic centres – the buildings that stand between Rupert and Bannatyne avenues on either side of Main Street – has impacted the vitality of our downtown.

The Manitoba Centennial Centre was a project begun in the 1960s aimed at reinvigorating the downtown. It includes the Centennial Concert Hall, the Manitoba Museum, the Planetarium and Manitoba Theatre Centre. The Civic Centre project had a similar goal, and it includes City Hall and the Administration Building (completed in 1964), and the Public Safety Building and the Civic Parkade (completed in 1966).

“As far as modern architecture is concerned, these buildings aren’t crappy,” said Galston. “Just as far as their conduciveness to the urban environment… they can’t add anything to urban life.”

When these buildings were constructed, the hope was that nearby hotels and businesses would renovate to cater to an upscale clientele, Galston said. But this was not the case.

“It was so inward focused. It was just such a major plopping down of something rather than working with what is already there,” he said.

In order to construct the buildings, a number of heritage buildings like those in the nearby Exchange District were torn down.

The previous City Hall – a Gingerbread-style Victorian beauty completed in 1886 – was also demolished.

Whereas the previous building had been tall with big doors that opened onto Main Street, the contemporary version is short and squat and turned in on itself.

“Anyone that passes by now is like, ‘Wow, that’s underwhelming and unwelcoming,” he said of the new building.

All of these projects also further divided the city, Galston said.

“It kind of created a gap between the north part of the city and downtown.”

“ We should forget about getting suburban visitors.

Peter Holle, Frontier Centre for Public Policy

‘Purifying’ our neighbourhoods

Like most North American cities, Winnipeg did not escape the drive toward land-use zoning of the early and mid 20th century.

Meant to protect land values by limiting how property could be developed, zoning prevented the arbitrary construction of noisy and polluting industrial and commercial structures around residential living spaces.

According to Marc Vachon, a geography professor at the University of Winnipeg, today most cities are moving away from the practice in favour of mixed-use neighbourhoods like the West End or West Broadway, where commercial space, apartments and houses exist in close proximity to one another.

At its zenith in the first decade of the 20th century, Winnipeg was one of the first cities in the country to experiment with the idea of zoning a whole neighbourhood as residential.

The area surrounding St. Mary’s Academy just west of Osborne Village, known as Crescentwood, was the first residential suburb in Winnipeg.

Today members of the Crescentwood Homeowners Association work to “preserve the intent” of the neighbourhood.

“It doesn’t have pollution or noise. It’s a little enclave, it’s your home,” said Jackie Greenhalge, spokesperson for the CHOA.

“There are plenty of places downtown to build or subdivide.”

Although neighbourhoods like Crescentwood have come to be seen as central, far-flung car-oriented suburbs around the city are all products of the zoning philosophy.

“It has gotten in the way of sustainable development,” said Vachon.

Vachon believes that zoning is useful but it is only one piece in the development puzzle.

“It’s just a tool, it is not planning,” he said.

Easing escape from the downtown

The one-way street design of downtown Winnipeg was implemented to ease transportation through the area, but the results were perhaps even better than anticipated.

“Downtown is set up for the suburbs,” said Peter Holle, president of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (FCPP), referring to the fact they can ease transportation to far-flung areas.

Holle is calling for a change back to two-way streets and for a reform of the downtown parking system.

In the late 1950s and early ‘60s the conversion was made to one-ways to enhance traffic flow, according to Fixing Winnipeg’s Downtown, a 2002 report by the FCPP.

Holle feels that downtown suffers because of the one-ways, but that changing them to two-ways would not solve the problem alone.

“We need to do what other places have done and make downtown an interesting place to live,” he said.

“We should forget about getting suburban visitors.”

Holle would like to see downtown become less car-oriented, which would encourage foot traffic and spur the development of storefronts instead of malls.

However, he admits that one-way streets have their appeal – pedestrians benefit because they only have one direction of traffic to watch for, which decreases accidents.

“There are some very substantial safety benefits,” he said. “It’s a trade-off.”

Curbing pedestrian access to Portage and Main

In the 1950s and ‘60s Portage Avenue was in its heyday – it was a destination.

According to Russ Gourluck, author of Going Downtown: A History of Winnipeg’s Portage Avenue, the intersection of Portage and Main was a hub of Winnipeg-style activity and an iconic meeting place.

In 1976, however, Winnipeg closed down all pedestrian access at the corner of Portage and Main, driving activity to the shops below ground.

This decision, according to Galston, was the symbolic death of Portage Avenue as a destination.

“[It] is big psychologically and symbolically,” he said.

The closing of Portage and Main to pedestrian traffic was indeed its symbolic death, but according to Gourluck, Portage Avenue had already suffered two fatal blows by 1976.

The first was the opening of Polo Park in 1959. Until Polo Park, the only place to shop was downtown. Polo Park was the first mall of its kind in Winnipeg. With free parking and no confusing one-way streets, Winnipeggers flocked to the shopping centre, marking the beginning of the end to downtown shopping.

The second factor was the termination of streetcar service in Winnipeg in 1955. With more and more people buying vehicles and the city ending transit services, public transit became known as a means of transportation for the disadvantaged, Gourluck said.

So by the time the intersection was closed, Portage Avenue was already in a slump.

All the big-ticket stores like Eaton’s and The Bay were located on the south side, and the north saw closures and a steady decrease in shoppers.

In 1987, as an attempt to revitalize Portage’s deteriorating north side, Portage Place was built. Portage Place as a remedy was not seen as controversial, but the building plans were.

“I had proposed that instead of [building] the structure right up to the property line… that a landscaped area should be planted and that would make a very charming addition to the downtown,” former city planner Earl Levin said.

As it stood, Portage Place was unable to compete with the shopping ease offered by Polo Park.

Portage Avenue, and Portage and Main as a hub of activity, continued to deteriorate. Today, although some stores have begun to move back into the area, it still remains largely disadvantaged.

Learning from our past mistakes?

Reflecting the sun’s rays, the MTS Centre’s glass paneling draws the glances of curious passers-by.

“One of the biggest issues was to try to be as engaging with people and the street as possible, that people would see what’s inside,” Ron Basarab, project architect for the MTS Centre with Number Ten Architectural Group, said of its design.

“There’s an invitation to come in from the street level.”

Finished November 2004, after almost 10 years of active discussions, the arena was billed as an ‘entertainment and retail mega-project.’

It was designed by Winnipeg’s Number Ten Group and Denver, Colorado-based architects Sink Combs Dethlefs.

With a number of entrances from all street corners, the skywalk walkways and large neon signs, the MTS Centre projects accessibility for the masses.

“It’s a completely different theory than the Centennial Concert Hall,” Basarab said.

But will the MTS Centre have a similar fate as the Centennial redevelopment? It’s hard to tell right now.

Taking up only one block and with a number of entrances, the Centre draws over 100,000 visitors every month, said Kevin Donnelly, the Centre’s general manager.

Another 100,000 use the Centre’s walkways monthly, linking it with the surrounding community, Donnelly said.

Yet paying visitors usually frequent the Centre during events like Moose games and concerts, or during business hours.

This was a squashed opportunity for the city to develop a complex that combined commercial and residential spaces, said Galston.

Instead, like Centennial Concert Hall, this is another area people utilize during events but largely avoid at night, he said.

Yet it also instills a sense of pride and boosts morale. People who drive past probably think it’s an improvement over the old Eaton’s building which it replaced, Galston said.

“Mind you, these people that say that, do they ever get out of their cars?”

Former city planner Earl Levin feels the same way.

“I really don’t think that is providing the same kind of impetus and the same kind of feeling as there would have been if they would have created a residential [area],” he said.

Published in Volume 63, Number 26 of The Uniter (April 2, 2009)