West End Snapshots: Saigon Park Memorial

Across the street from the Ellice Avenue entrance to the University of Winnipeg, there’s a little place called Saigon Park

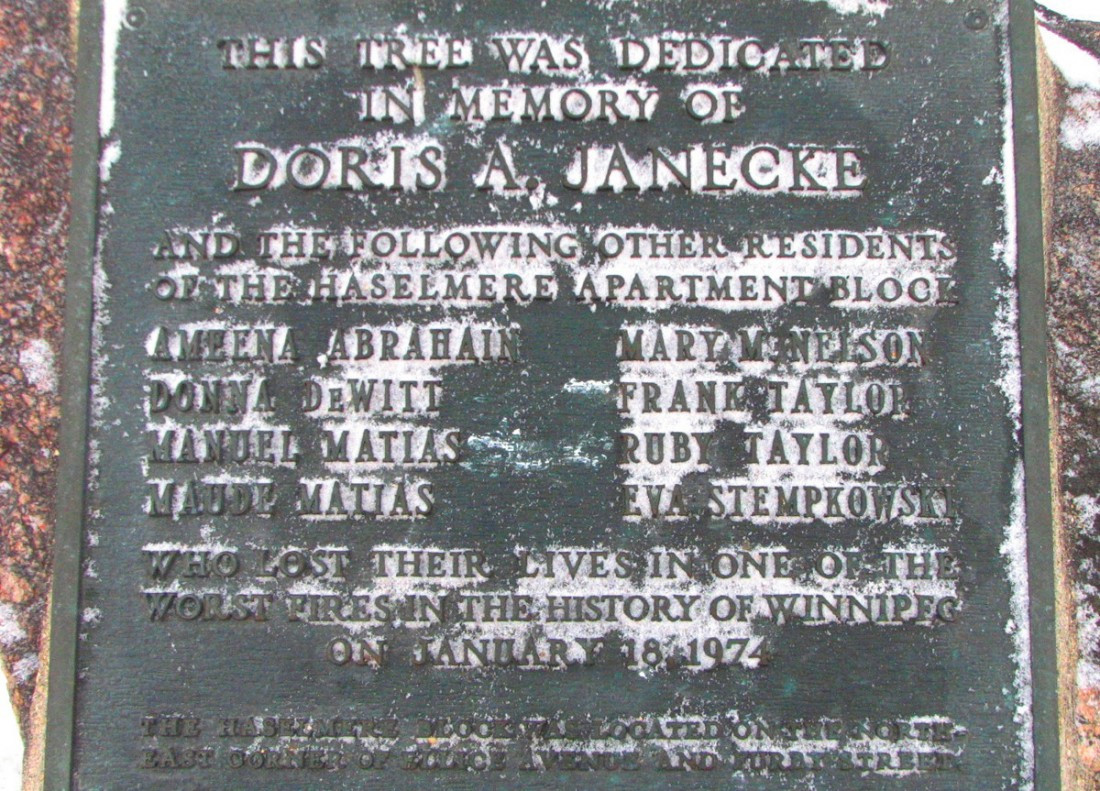

Across the street from the Ellice Avenue entrance to the University of Winnipeg, in what is called Saigon Park, there is a memorial tree and stone commemorating the nine people who were killed in the Haselmere Apartments fire of 1974. It was a blaze that led to a showdown between the City and landlords and changed how Winnipeg’s fire code was enforced.

At around 1:15 a.m. on the morning of Jan. 18, 1974, a passing motorist noticed smoke coming from the 1910-era three-storey walk-up located at 559 Ellice Ave. at Furby S. He drove to the nearest payphone to call it in, and “by the time I got back, everything and everybody was in hysteria. Some people were still yelling from the windows and some people were jumping.”

By the time the fire was extinguished later that morning, nine people ranging in age from 19 to 70 were dead. It is believed to be the second deadliest fire in our city’s history.

The tragedy was compounded by a couple of factors. First, it was discovered that a man who had been staying over with his uncle in one of the suites intentionally set the blaze after an evening of drinking. Then, at the coroner’s inquest into the deaths, it was revealed that the building had no fire protection measures in place and that it wasn’t required to have these measures under the city’s fire code.

The Haselmere had no sprinklers, fire alarms or smoke detectors. Internal stairways were not shielded by a firewall and the exterior fire escapes were unusable. The reason for these lapses had to do with a grandfather clause in the city’s 1911 fire code which exempted apartment buildings that pre-dated it. Former fire chief Jack Coulter recounted to the Free Press decades later that “It (the Haselmere) was just built to burn.”

Less than two weeks after the fire, city council tasked the city’s Buildings Commission with tackling these deficiencies and on May 15, 1974, it began enforcing the fire code for all buildings, regardless of when they were built.

Landlords fought back. They argued that the changes would cost them tens of thousands of dollars per building and end up putting many of them out of business. Some raised the dark scenario of a severe housing squeeze as landlords walked away from their properties or demolished them rather than upgrading. They went to court to challenge the commission’s ability to retroactively enforce the fire code and won.

The city had to go back to the drawing board to create a brand new bylaw giving the commission the authority to enforce the fire code in existing buildings. That bylaw passed in August 1975 and the long process of inspecting the city’s 1,750 apartment blocks, 250 of which were constructed before 1911, began. It took years to complete.

It was an awful fate for the nine victims but their deaths on that awful night in January 1974 has undoubtedly saved the lives of countless others in apartment fires that were prevented.

Christian Cassidy explores local history at his blog West End Dumplings

Part of the series: The Urban Issue 2015

Published in Volume 69, Number 26 of The Uniter (March 25, 2015)