Vaccine confronts ethics

COVID-19 vaccine allocation raises ethical implications

Who will get the vaccine first? Should a vaccine passport be mandated for those who wish to travel?

Many technological advances that have come out of the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to the hard sciences – but the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines extends beyond that scope. The question of who gets what, when and how demands rigorous ethical examination.

Katarina Lee-Ameduri, a clinical ethicist at St. Boniface Hospital, says two key ethical concerns arise out of the COVID-19 vaccine: one of development and another of allocation. Now that several COVID-19 vaccines have been furthered from the development stage into allocation, she says the question of how vaccines are distributed is crucial.

“From an ethics lens, accessibility and risk are the two things that I’m most concerned with,” Lee-Ameduri says.

In Manitoba, like many other places in Canada and around the world, vaccines are currently being allocated to those who work with people who are most vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19. That includes healthcare workers, long-term care workers, correctional centre employees and those who handle COVID-19 in a laboratory setting.

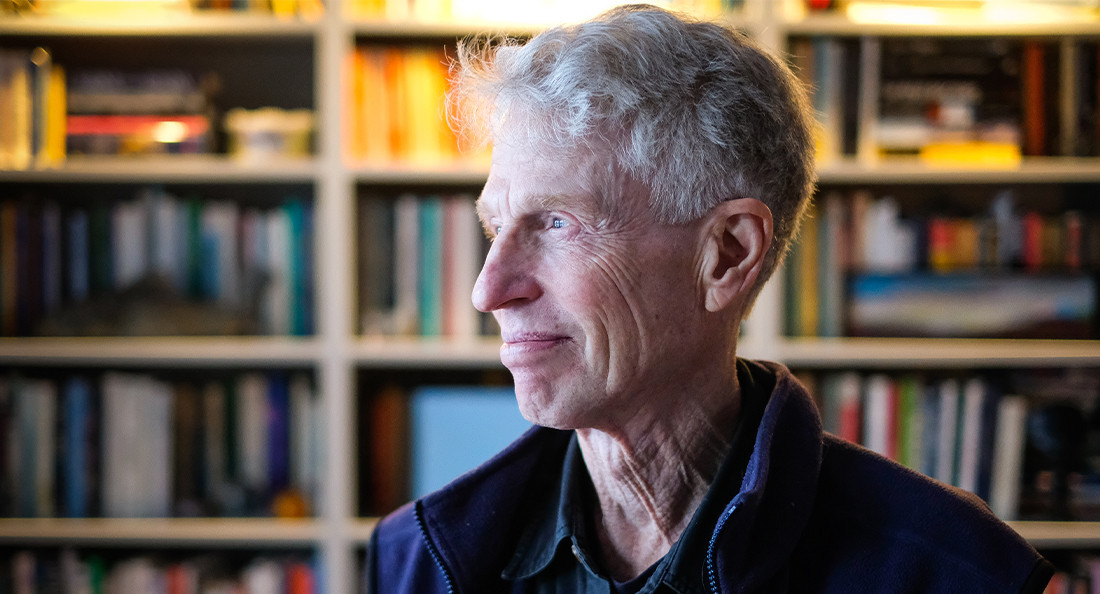

“The consensus pretty well everywhere in Canada, and probably shared internationally, is that the criterion we should use is who is the most vulnerable,” Dr. Arthur Schafer, a bioethicist and the founding director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics at the University of Manitoba, says.

In the field of bioethics, Schafer says there are a number of principles and frameworks for making ethical decisions in healthcare policy. He says one example is the principle of harm minimization, which supports the idea that those who work with those most vulnerable to COVID-19 should be given priority.

“We want to use the vaccine in a way that will produce the greatest benefit to those who are most likely to suffer the greatest if they become infected,” he says.

Glancing into a time when the vaccine is more widely available, some have tabled the idea of a “vaccine passport.” This would grant those who have been vaccinated mobility privileges such as travel and attending concerts.

Schafer believes this will raise another series of ethical questions. He says there is still uncertainty around how long the vaccine will grant immunity, and whether one could still be infectious to others.

“Until we know that, which presumably we will in the next few months, the idea of the vaccine passport is not one that would be very useful,” Schafer says.

Lee-Ameduri says that while the logistics of vaccine distribution will likely get more efficient as time goes on, she also suspects that the question of who will receive the next round of immunizations could become more complicated.

“If I’m a 70-year-old but I’m very, very healthy, but there’s a 65-year-old who has a lot of comorbidities and health conditions, should the 65-year-old with the health conditions take a greater priority?” she says. “That opens up the question of, well, is age the appropriate mechanism?”

With great technological advances comes the necessity of ethical questioning. As the trajectory of the pandemic falls closer to “normalcy,” ethics will continue to play an inescapable role.

Published in Volume 75, Number 16 of The Uniter (January 28, 2021)