This is not Hollywood

Documentary shows the colourful, exploitive and explosive low-budget cinema driving world’s third largest film industry

Where slums sit across skyscrapers and 500,000 people commute in and out of the city each day, the world’s third-largest film industry is operating with open public auditions and self-financed projects. Often described as “the answer to CNN,” Nollywood Babylon explores Nigeria’s film industry as it employs amateur writers, first-time actors, self-taught directors and apprenticing film crew.

“We don’t even want to go to Hollywood anymore,” says actress Omotola Ekeinde. “We want to make Nollywood the best and the biggest African industry in the world.”

Hollywood films, which were first introduced by colonizers “so that Nigerians knew what was going on in the world,” have become an expensive import, leaving only three working theatres in Africa’s largest city, Lagos. Today, 2,500 films are produced every year, using a budget under $15,000.

Billboards and posters advertise various genres, from traditional stories to modern comedies. Blockbuster hits are sold in Lagos markets and distributed throughout Africa, where workers from other African countries, such as Kenya, are starting to come to learn the trade.

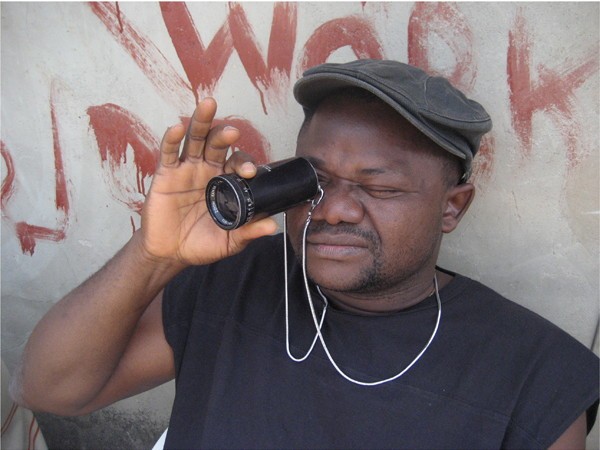

The film follows Lancelot Imusen, who is as passionate as any Hollywood director, though he never went to film school.

During one especially rushed day of filming, in which he shoots 59 scenes, Imusen lets loose on camera.

“You didn’t pan on time. Why is he jerky? The cable … please, that cable boy. I will break your head.”

Like its American counterpart, Nollywood is not free of critique. Not for its portrayal of violence or its depiction of women, but for exploiting a seemingly impossible target audience. The movies in question target deeply religious audiences, who mainly live in poverty, using what is arguably storytelling which is overtly inspirational.

“There isn’t enough attempt to see the implications of the struggle between tradition and modernity. They have been taken over, for instance, by born-again Christians … away from enlightened nation and society building,” says writer Odia Ofeimun.

Whatever the implications of these films might be, Nollywood Babylon provides an insightful look at the incredibly popular industry, the chaos and culture of Lagos, and Nigerian storytelling, from its film-making to its unique marketing.

The documentary is worth watching, not only for its criticisms or the ever-animated filmmaker Imusen, but also for its rare samples of Nollywood’s impressive and unique catalogue of films.

Published in Volume 64, Number 8 of The Uniter (October 22, 2009)