The Forbidden Room

Plays Oct. 9 to 11 and 14 to 18 at Cinematheque

Guy Maddin’s movies have never been easily digestible. His use of ancient film techniques and subversion of conventional narrative have made him one of the most challenging filmmakers, and also one of the most interesting.

His newest film, The Forbidden Room, which is his first feature co-directed with Evan Johnson, pushes his style further than it’s ever gone. From the opening credits, which seem cobbled together from broken fragments of prints of a long-lost film, it’s clear that The Forbidden Room is impossible to pin down.

Indeed, lost films are central to the movie’s premise. Press materials have described the film as a “Russian nesting doll,” a maze of films within films, within films. The premise of each mini-movie is inspired by real films from history which are considered lost. Maddin and Johnson take titles or synopses, like The Red Wolves and The Strength of a Moustache, and turn them into hilarious nightmares.

The movie feels like new territory for Maddin. It’s unclear how much of that comes from Johnson’s input and how much comes from Maddin’s famously twisted brain. Nevertheless, The Forbidden Room feels like Maddin’s most ambitious film. It’s almost entirely in colour. The fact that this is remarkable is a testament to Maddin’s place in cinema.

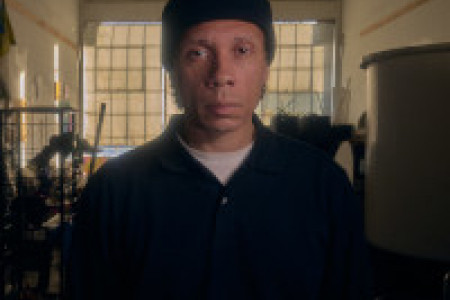

The cast includes standouts like Roy Dupuis as a woodsman-in-training (a “saplingjack”), Udo Kier as five or more phantasmic figures and the great Geraldine Chaplin as a sort of German expressionist Wicked Witch of the West who wields a whip and yells “Shame!” at a man obsessed with buttocks. She’s credited as “The Master Passion.”

Buttocks are worth mentioning here, and not just because they’re the subject of a musical number early in the picture. The Forbidden Room is rife with bizarre and funny psychosexual symbolism. At one point, a troupe of saplingjacks venture into a pink cave. At another point, a train takes a ride through a broken pelvis.

Maddin and Johnson understand and explore sexual repression in a way few other filmmakers can. They understand the cultural link between sex and shame that we’ve spent decades trying to erase, but can still pop up in the most humiliating places.

Maddin’s familiar use of forgotten film techniques goes to entirely new places here. The film is shot digitally in a wide aspect ratio, but the screen is always pockmarked with inexplicable flaws and image distortions. Sometimes the whole screen appears to be on fire. At other times, they conjure dead or near-dead formats like two-strip Technicolor or the radio play. The 1920s wardrobe, 1930s miniatures and archaic cultural touchstones underscore visual approaches that wouldn’t feel at home in any earthly decade.

The resulting tone of the film is something new. It’s hilarious. It’s the best kind of exhausting, like when you just ate too much of a delicious meal. At its best, it feels borderline satanic. It’s like someone found a way to film a nightmare. Not Maddin or Johnson’s nightmare, but the nightmare of cinema itself.

Published in Volume 70, Number 5 of The Uniter (October 8, 2015)