The Column

Dry Wit

When I first got sober and worried about people’s reactions, a wise friend told me that other people’s responses were more about them than me.

Recently, my sobriety has been coming up more often in everyday conversations, and I’ve noticed some patterns in people’s responses. Over the winter I discovered that my body reacts horribly to yeast, so now yeast-based foods – bread, croissants, pizza crusts – are a total no-go.

I ask about yeast when I’m ordering food or planning shared meals. Most of the time it’s a non-issue, but when people do respond, it’s usually an incredulous, “So you can’t eat bread … ever??” After a moment of computing, this may be followed by an equally stunned, “Wait, so you can’t have beer either?”

Can’t have beer came far after won’t have beer, but with a new dietary requirement, the no-beer thing is coming up more often.

Food allergies (or intolerances) and sobriety are definitely not the same thing, but they can bring out similar reactions from others. These reactions reflect some societal attitudes around “going without” and the assumption that a life without bread (or beer) must be a sad and sorry state.

I’ve seen an increasing trend in Western society to restrict all kinds of food and drink unnecessarily, to diet or cleanse, to label foods good/bad or “clean”, to make a visible show of constantly striving for the golden chalice of Perfect Health. The things we do and don’t put in our bodies have become symbolically loaded.

It’s less common to see food as neutral anymore – as something to fuel us, or even something to be enjoyed in all its forms.

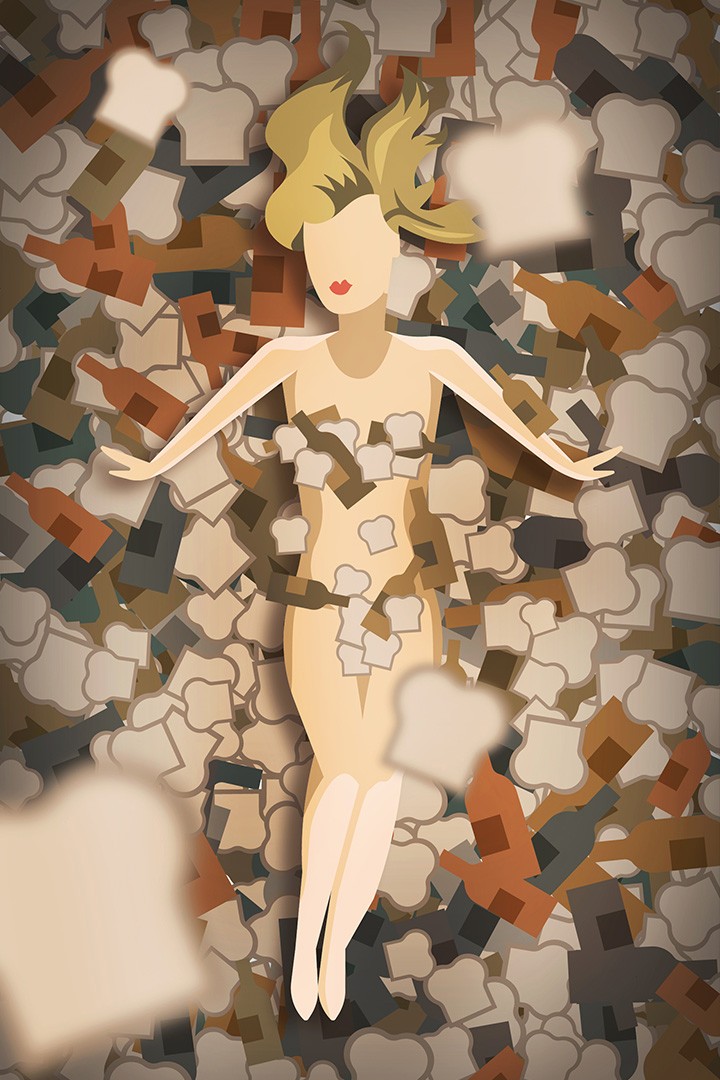

It’s more common (and trendy) to experience periods of unnecessary deprivation of whole food groups. So it’s no surprise that when I say that I can’t eat or drink a thing, these facts are processed within a framework of deprivation by some folks. Perhaps they imagine a giant baguette or bottle-shaped crack through my soul.

Periods and patterns of forced restriction can also make the banished object more desirable, so it’s no surprise that carbs – and especially bread – are alternately demonized and revered. As clean eating movements liken bread to poison, attempts to reclaim this simple staple turn it into a new idol.

But I don’t see quitting drinking or being unable to eat yeast as forms of deprivation or missing out. Coming to these decisions (and discovering these reactions) stemmed from tremendous acts of self-care. They marked moments when I was finally able to listen to what my whole self – physical, emotional, mental and spiritual – needed, and what simply wasn’t working anymore.

When I quit drinking, I learned that while it seems like booze is the glue that holds our lives together, it isn’t. Without liquor, life didn’t fall apart – in fact, it became more cohesive. And that surprised me as much as anyone.

That lesson served me well when I learned that yeast also needed to get the boot. I had faith that after the initial hump, the trials of yeastless eating would simply become normal. Life with wraps, and muffins and other non-risen foods (including some kinds of bread) really isn’t so bad.

So when someone is stunned that I can’t have most breads – or beer – then I just tell them the truth: “Well, I don’t drink, so that part was easier.” How they respond to that is up to them.

Anastasia Chipelski is the Managing Editor at The Uniter and casual baker of soda bread. She’s been known to give impromtpu lectures on the difference between yeast and gluten.

Published in Volume 71, Number 1 of The Uniter (September 8, 2016)