Smudging in the streets

Midnight Medicine Walk hopes to bring healing and awareness

Walking down Selkirk Avenue, Winnipeg’s youth exploitation epidemic is hard to ignore.

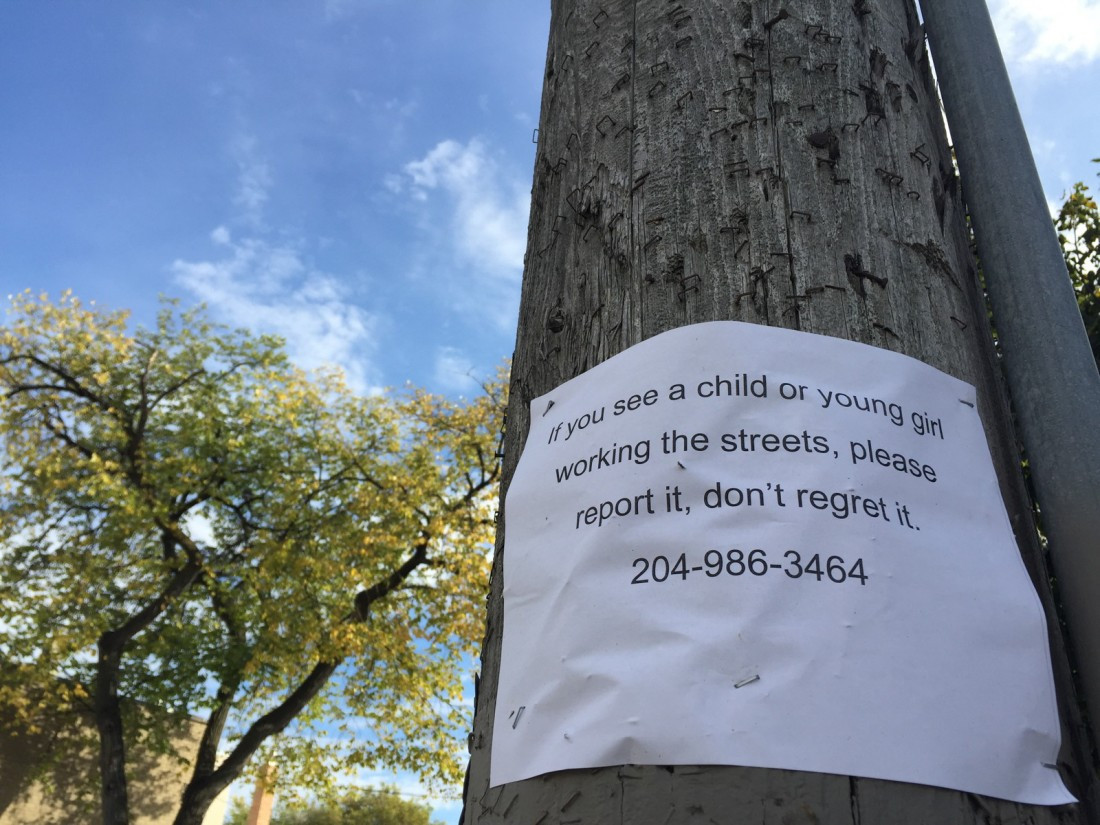

Signs in the windows of community organizations plead: “Don’t buy sex from kids.”

One grassroots event hopes to combat this issue.

After years of community organizing with Aboriginal Youth Opportunities (AYO), a youth movement from the North End, Lauren Chopek approached the group to help her get an idea off the ground.

Chopek wanted to start a healing walk that takes place at night, where participants can engage with the people they’re reaching out to. The walk has an added personal significance for Chopek. She went missing multiple times in 2011 as she battled a drug addiction.

The Canadian Centre for Child Protection says approximately 400 children and youth are being sexually exploited on the streets of Winnipeg each year, a figure that includes only visible sex trade exploitation. The majority of sexual exploitation victims are female. Most are also indigenous.

For Chopek in particular, the issue hits close to home.

“I’m young, and I was once on the street,” she says. “To do a full turnaround and then to be there for those people… means a lot.”

Chopek, now an 18-year-old child and youth care student at Red River College, also hopes to send a strong message.

“I wanted to raise awareness to the people on the street that we do care,” she says. “But I also wanted to raise awareness to the people that prey on these young people that we’re not going to just sit around and let it happen.”

More than that, she hopes that events like these will help challenge stereotypes.

“Lots of people just drive by and think negative things about these people, but they don’t realize that the girl standing on the corner could only be 14-years-old,” Chopek says. “They don’t think about the fact that she’s someone’s daughter, someone’s sister, someone’s friend.”

“AYO was a good fit because we are committed to breaking stereotypes,” Michael Champagne, the founder and organizer of AYO, says. “We also feel passionately that all citizens must do what they can to make our communities safer.”

Lori Buxman, who attended last year’s walk and used to live in the North End, is hopeful the event will help create change in the community.

“I’ve probably seen girls out there that are 12- and 13-years-old,” she says. “I don’t know if anything has changed...not enough.”

One of the signature aspects of the medicine walk, now in its third year, is smudging the streets with sage, an especially symbolic action in this context.

“Sage is supposed to cleanse and remove the negative,” Chopek explains. “And that’s what we’re trying to do with the walk.”

While the medicine walk primarily aims to bring healing to those being sexually exploited, Chopek also hopes to challenge common views held about indigenous people.

“It wasn’t even that long ago that residential schools happened,” Chopek says.

She notes she was born the same year the last federally-run residential school closed.

“Lots of people say that it happened so long ago and we should just stop talking about it,” she says. “But there’s this (trans)generational trauma...it still affects people’s lives today. It affects my life. It will probably affect my children’s lives.”

While challenging racial stereotypes often seems overwhelming, Chopek remains hopeful.

“It’s hard to say how much of an impact what I’m doing will make, but I hope that people that are on the street will see us and know that we care,” she says. “And maybe that will make a difference.”

Published in Volume 70, Number 3 of The Uniter (September 24, 2015)