Small Talk

We are not all sisters… and that’s OK

First wave feminism had a clear, political goal: get women the vote.

Second wave feminism had more varied aims and worked within other movements, like the civil rights and antiwar movements. Second-wavers believed in women as a social class, emphasizing the need for solidarity and sisterhood to bring about social change.

Third wave feminism is a loosely defined term that represents a variety of different belief systems. It addresses a wide range of perspectives that other women’s liberation movements failed to address, namely, a rejection of collective female identity.

The idea of universal sisterhood is problematic because it implies that there are universal experiences shared by women – like motherhood, menstruation, or pregnancy. And by believing in these universal experiences, we rely on a fixed notion of womanhood which is often determined biologically.

See the problem? Thinking about gender in essentialist or reductive terms automatically excludes or edges out people who don’t fit the profile: women without uteruses, who aren’t mothers, who don’t menstruate. While gender essentialists certainly exist within the feminist community, I personally can’t get behind a movement as exclusionary as the one it is working against.

Intersectionality, on the other hand, stresses interactions between class, race, gender, sexual orientation, ability and other aspects of identity while recognizing how these all factor into larger systems of power and oppression differently.

A white woman is not working with the same deck of cards as an Indigenous woman in this city or that of a woman living half a world away. To claim that “we are all the same” not only grossly minimizes the struggles of others, but it dismisses the belief that we are all the experts of our own lived experiences.

This sort of “we are all one” essentialism often gets co-opted by white women attempting to speak for, and over, women in other circumstances. Nicki Minaj has been an outspoken voice for black women in the music industry. Minaj is highly critical of the ways this same industry commodifies and sexualizes them while overlooking their success in favour of slim, white, “acceptable” bodies.

In response to a series of tweets about her most recent MTV Video Music Award snub, Miley Cyrus criticized Minaj in the press for her tone, implying that Minaj was, in effect, being a sore loser. Cyrus’s response suggests it was a fair race to begin with, that there is an equivalency in their struggles as women in the music industry. She glosses over Minaj’s experience as a black woman in America, in the music industry, and in the media, which is altogether different from Cyrus’s experiences.

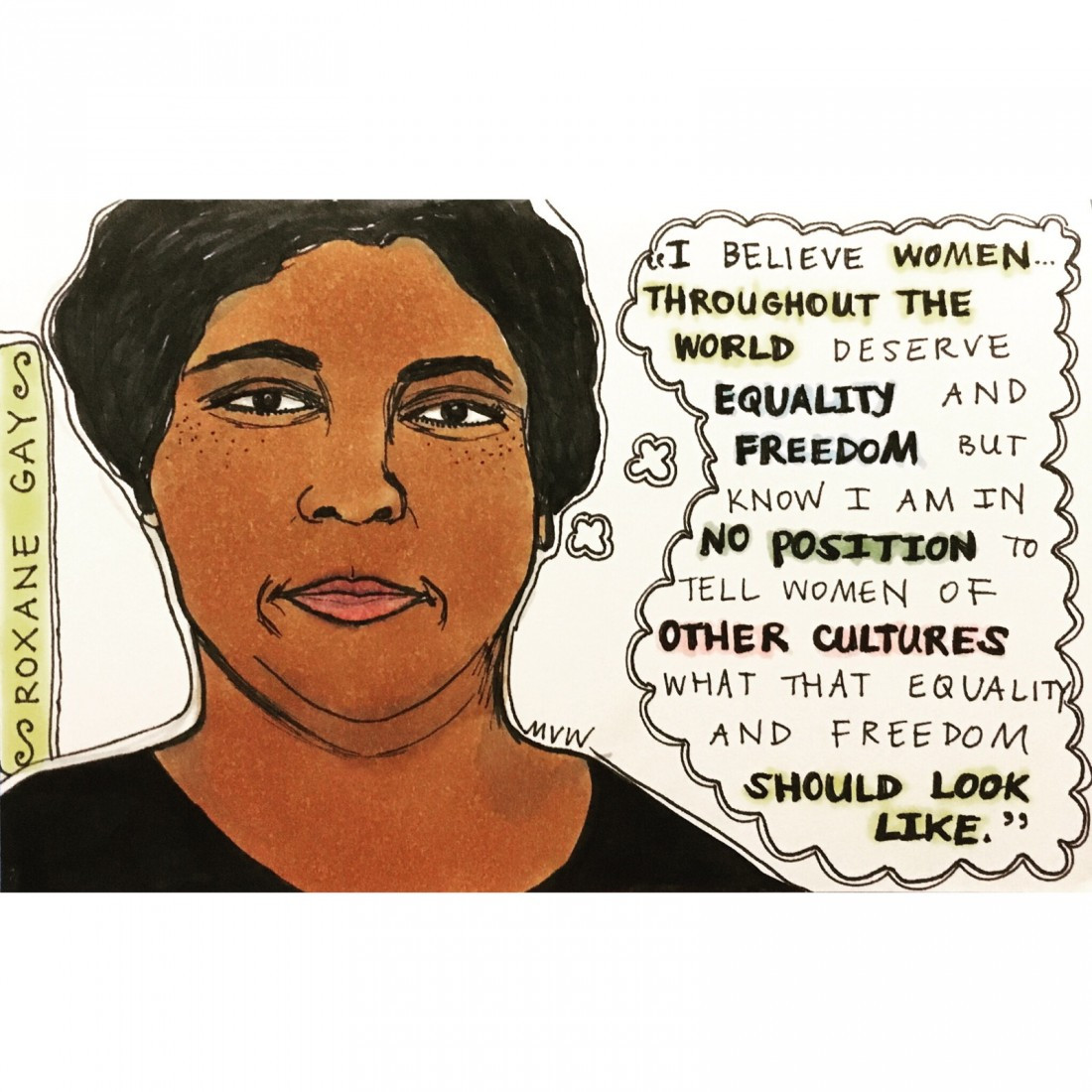

Criticizing other women for the choices they make in response to their myriad oppressions undoes the long history within the feminist movement of fighting for autonomy. On the other hand, when we assume that all women who live or look differently than we do are oppressed, we strip them of agency or choice, and also position ourselves as more liberated, educated and not equal. It means we are not, in the end, the same.

That’s not to say we can’t feel connected to one another, or have compassion for others. It also doesn’t mean our experiences won’t overlap sometimes. The thing is, patriarchy oppresses almost everyone – women, men who aren’t the “right” kind of masculine, and especially those who don’t fit comfortably into either gender category.

But the good news is that equality doesn’t have to mean sameness. Rather than yelling about how much we’re alike, we could learn about our differences by supporting one another as allies instead of suffocating each other as sisters.

Dunja Kovacevic is a writer and co-founder of Dear Journal. Issue 1 is now available for purchase at Music Trader and online. Connect with them on Instagram: @dearjrnl.

Published in Volume 70, Number 14 of The Uniter (January 7, 2016)