Raising chickens in the city

It may not be legal in Winnipeg, but urban chicken farming is catching on in other major cities

If you haven’t heard clucking in your backyard yet, you may soon. A growing number of cities are in the process of permitting urban egg production.

It hasn’t hit Winnipeg yet, but the trend is sprouting up in surprising numbers: New York, Chicago, Seattle and Portland all promote the raising of chickens within city limits.

In Canada, Vancouver is working on by-laws to allow urban chicken farming, following the lead of already legal chickens in several Lower Mainland suburbs.

Presently it’s legal to raise chickens in Victoria, though in Toronto it’s illegal. Vancouver, Waterloo, Toronto and Calgary all have organized advocacy groups that try to influence municipal regulations.

Calgary’s advocacy group, “Calgary Cluck,” organizes through Facebook.

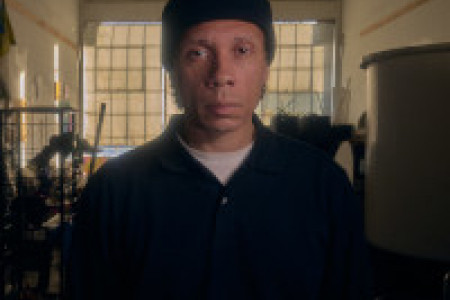

One member’s online moniker, “Mary Contrary,” belies her interest in guerilla farming and pushing boundaries. She received several warnings and finally a ticket for her three hens after an issue over an overhanging bush led her neighbour to “a city bylaw phone call spree.”

Contrary plans to fight the ticket.

“I believe it’s within in my civil rights to have these eggs.”

Advocates of backyard chicken farming list its benefits as improvements to health and diet, political influence, environmental sustainability and family fun. Contrary refers to her chickens as “girls” and said it is her children who benefit from the fun and responsibility of raising their own food.

Heather Havens, who has three illegal hens in Vancouver, said she believes in the health of her poultry. She insists on the level of cleanliness obtained by raising her own food, and on the biological impossibility of disease like Avian Flu spreading in small backyard flocks.

Serious poultry born disease “needs factory farming conditions with unhealthy chickens in an unhealthy environment,” she said.

Mary Contrary was honest about other domestic risks, like “When the chickens bust loose and eat all my lettuce.”

“ I believe it’s within in my civil rights to have these eggs.

“Mary Contrary,” Calgary-based urban chicken farmer

Michael Levenston, the executive director of Vancouver’s City Farmer Society, connects urban chicken raising to a more general interest in eating close to home and a more comprehensive understanding of food sources.

“We’re environmentalists,” he said, and urban farming gives the farmer a “better understanding of their environment, soil, air quality and what’s in your food.”

Levenston has been part of the organization for over 30 years, and in that time has been part of initiatives to create community gardens and composting projects in the city of Vancouver.

City farming, in both the vegetable and poultry capacities, poses its own unique challenges. Levenston lists vandalism and theft as problems.

“[But] you’ll probably lose your bike before you lose your tomatoes,” he said, adding that the City Farmer Society takes a “philosophical” view on theft: “It’s sharing.”

In cities where chicken raising is legal, bylaws are generally restrictive so as to ease the fears of noise, smell and sanitation. In Vancouver, the proposal allows for a maximum of five hens—roosters are illegal. Havens, who is a key player in Vancouver’s pro-chicken campaign, insists that with so few chickens, excrement is a negligible issue, and the noise is minimal.

Winnipeg does not have an advocacy group, and according to the City of Winnipeg’s Animal Services, few inquiries have been made in the past years.

If one were to try to raise chickens in Winnipeg, Animal Services said that a fine is only issued after several warnings. The punishment for non-compliance once a warning is issued can be anywhere from $50 to $1,000.

Speaking on a condition of anonymity, a city pound spokesman at Animal Services said warnings are sufficient and gentle, if one is not “abusive to people who do inspections.”

“They give you a month to clean up” before any follow up action is taken, he said.

So who might be keeping chickens in Winnipeg now?

“Sometimes it’s cultural,” the spokesman said.

Perhaps the international communities in Winnipeg, unaware of local bylaws, continue practices culturally and legally condoned elsewhere. Unlike other cities with advocacy groups and civilly disobedient farmers, however, he said Winnipeg has not seen an increase in complaints about chickens in the city.

Levenston and Mary Contrary had different views on the growing interest in urban farming in their cities.

“People listen and pay attention to the media,” Levenston said, and to political leaders who farm. “Mrs. Obama and Queen Elizabeth have started vegetable gardens.”

He added that people do “whatever they can to help themselves in a recession.”

What’s suggested for Winnipeggers wanting to start an urban chicken campaign?

“Be organized,” said Havens.

When Havens approached the Vancouver city council, she was educated about the issue and anticipated objections. Havens thinks that resistance to urban chickens is an issue of education, and now gives “chicken talks” helping people learn the ropes of city farming.

Published in Volume 64, Number 1 of The Uniter (September 3, 2009)