Putting Redman in a seven-foot deep hole

An oral history of visual hip-hop

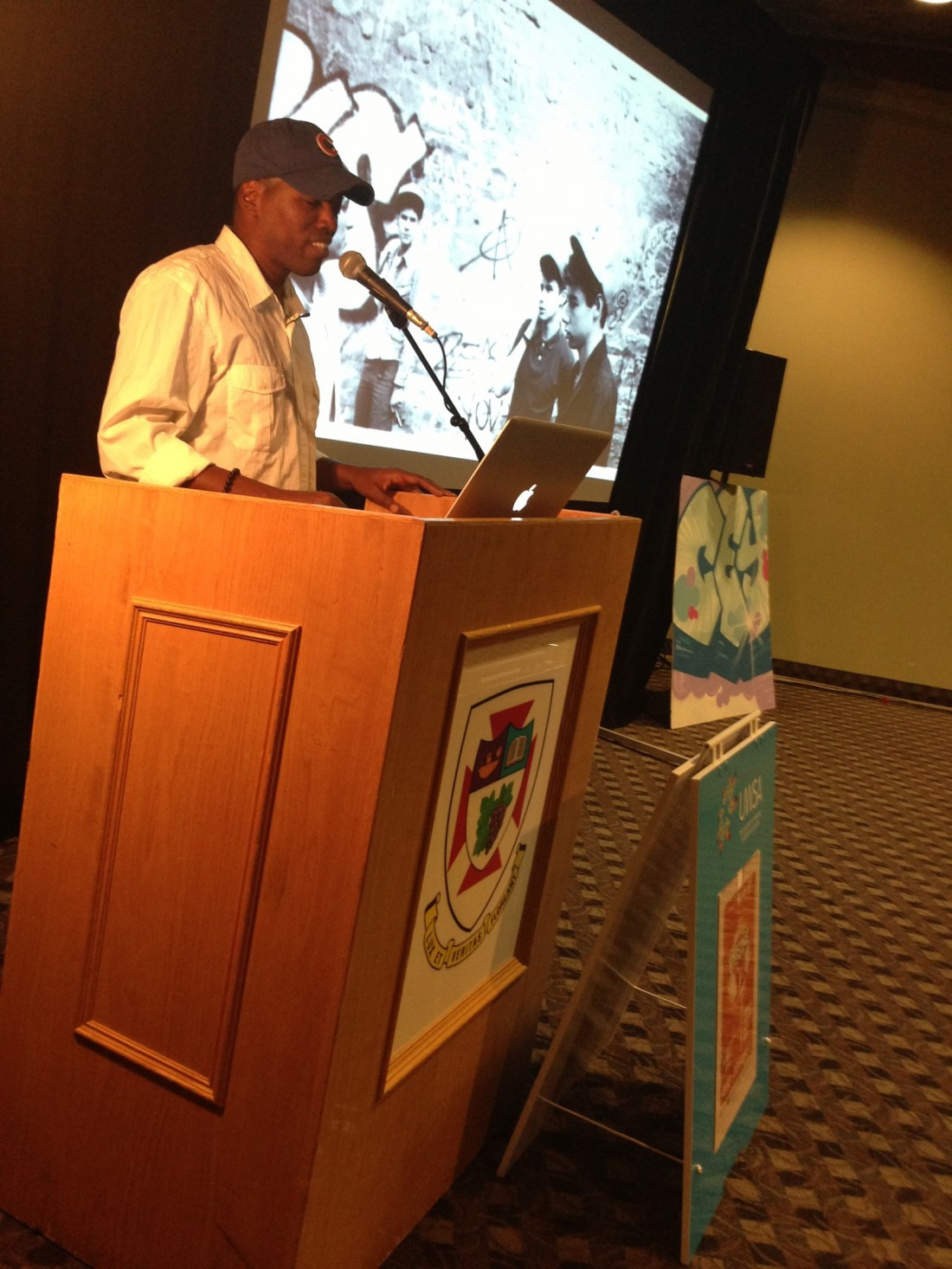

New York’s Cey Adams, founding Creative Director of Def Jam Records, spoke in the University of Winnipeg’s Riddell cafeteria on Thursday, October 3, 2013 as part of the UWSA's Freestyle Festival. I enjoyed an evening of colourful tales of rappers from the 1980s and early 1990s, artists whom Adams had worked or rubbed shoulders with during his tenure at Def Jam.

The artist is a practiced story-teller, and unabashedly listed his accomplishments while coyly toying with some self-deprecation to take the edge off.

“So ‘78-’79, I go pro. I'm a professional graffiti artist. What's a professional graffiti artist? Somebody who leaves his house. In ‘75-’76? I'm tagging my notebook, my dresser.” Cey explained that some of his vision came from his multi-genre taste, coupled with an undercurrent of confidence in hip-hop as a cultural movement.

“I wanted to match the art of Pink Floyd, of The Doors,” he says. “I knew what we were doing wasn't bastard music, it was good. So, to put three rappers in front of a brick wall, in B-boy poses... I don't want to do that.”

His stories ranged from hilarious to straight-up cool. “You guys know that song ‘Empire State of Mind’”? he asked, with either a convincing deadpan, or a gross overestimation of Winnipeg's insularity (Yes, Cey. The song has 180 million YouTube hits. We know the song). “That line about 560 State St., that's where I was living when Jay-Z moved into my building.”

What? Cool.

“And he's throwing parties in the courtyard, and I'm seeing the guys from De La Soul, Brand Nubian, and I'm thinking 'Wow, that guy really knows a lot of people! Must be some kind of promoter or something.' It wasn't until Russell [Simmons] pulls me into this meeting with Jay, that I realize 'Ohhh,' he's the guy from Roc-A-Fella!”

Adams has an affinity for weirdos, too. “Redman, he was kind of a maniac. But he was open to really insane ideas!” The cover of Redman's second album, Dare Iz a Darkside, shows the emcee buried up to his neck, screaming to the sky in ferocious anger. “Now, this is before Photoshop,” he reminded the audience. “What you're seeing is what we did. We dug a seven-foot deep hole, and Redman just got down inside of it. And then we filled it back up.”

Funnier still were Cey’s experiences with the rappers he didn't quite understand. “DMX,” he mused, “DMX was the scariest guy I have ever met.” Scary, with a particularly unique style of salutation. “The thing DMX would do when he meets you... is head-butt you.

“So Russell brings him to meet me, and I get the head-butt and he's all 'WASSUP, DAWG?!' And I'm thinking: 'What was that? I'm working. I'm at work.' And then I'm thinking 'I am not getting paid enough to be here.'”

The personal anecdotes were my favourite part, but Cey was most passionate when talking about the concepts and history of album artwork, many of which were displayed on a screen behind him as he spoke. He reminisced fondly about working on Public Enemy's Fear of a Black Planet. He described how excited he was when Chuck D approached him, telling him “We need a logo, so people remember us!” To Cey, this symbolized a movement beyond b-boy posturing and into more substantive, creative branding. Chuck D brought him a rough sketch of his concept for Fear of a Black Planet, but when Cey pressed him for details on the look, Chuck D retorted “That part's your job!

If there was one thing that bothered me during Cey's talk, it was his portrayal of Foxy Brown, the one female artist he talking about working with. He described her good looks, her emotional temperament and her love of shopping. Brown may very well have been all of those things – her Wikipedia page certainly confirms the feistiness – but I expect there was more depth to her than the stereotypical sexy, fashionista babe image. Even the unruly DMX was coloured with a more sophisticated palette. His aggressive intensity was mentioned, but Cey also called him a “conceptual” thinker, who could understand the vision of an artist and run with it. I can't help but see Brown's gender affecting her limited portrayal.

That complaint aside, what I took away from the talk was that Adams cares: He cares about the role art plays in the world, he cares about the work that he does, and he cares about people. During the question and answer sessions that followed his talk, what began as a question from a U of W student quickly became a rambling but sincere confession on the student's lack of direction in life, and he entreated the speaker for guidance, who engaged with him willingly and compassionately.

“How old are you?”

“Me? I'm 21,” the student responded.

“You know what the best thing about being 21 is?”

“Um.. what?”

“You're 21.” The crowd laughed, but Cey wasn't letting off with just a quip. He continued with some heartfelt, if slightly platitudinous, advice, “Being young is one of the most amazing things in the world. Cause you have time to figure it out. Cut yourself a lot of slack. Don't worry what others are doing. What works for them might not work for you. It will come to you. I'm not saying it'll be easy. I was lucky, I was born with this inside me, knowing what I wanted to do. In 1983, Russell Simmons, no one knew him. Opportunities don't always come with a sign. Follow your heart, you have to believe in that.”

Cey's playful, unpretentious story-telling and balance between the artistic and the personal made for an evening well spent.

Fabian Suárez-Amaya has never head-butted a business partner. He is studying Education at the University of Winnipeg.