Practically speaking

Why studying the humanities is still worth your time and money

“And what do you intend to do with that?”

This seems to be the inevitable response one receives after proclaiming interest in pursuing an arts degree. Enrolment in the humanities at many schools is falling – one has only to gaze at the state of University of Winnipeg’s Classics and Philosophy departments to confirm this.

The cause falls to growing popular views that the natural sciences raise more apt minds, that the arts are not objective and that the humanities have no practical use.

Clearly though, these things are all untrue.

The practical uses of both the natural sciences and the vocational arts are self-evident. The practicality of the humanities, however, seems to be hidden away.

While both the sciences and the humanities share a similar methodology – the discovery of facts and the analysis of their relations – it is here that their similarities end.

The scientific method teaches that, in order to make a good choice, one must be aware of all observable phenomena – that the absolute must be known.

Unfortunately, such is hardly the case in real life. In fact, some of the most significant historical decisions have been made under circumstances in which certain facts were inaccessible.

Consider the decision once faced by American President Harry S. Truman regarding the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. In this instance, scientists were able to estimate the range of the atomic blast and its probable damage.

However, the full effects of the device were still, in part, unknown and the social implication of making such a decision were far from scientifically predictable. Truman, thus, was faced with a decision with no absolute outcome.

Indeed, it’s unlikely that most people will ever have to make such demanding choices. Still though, many of life’s most trying situations require one to reason without the luxury of scientific decisiveness; love, marriage, birth and death all fall into this category.

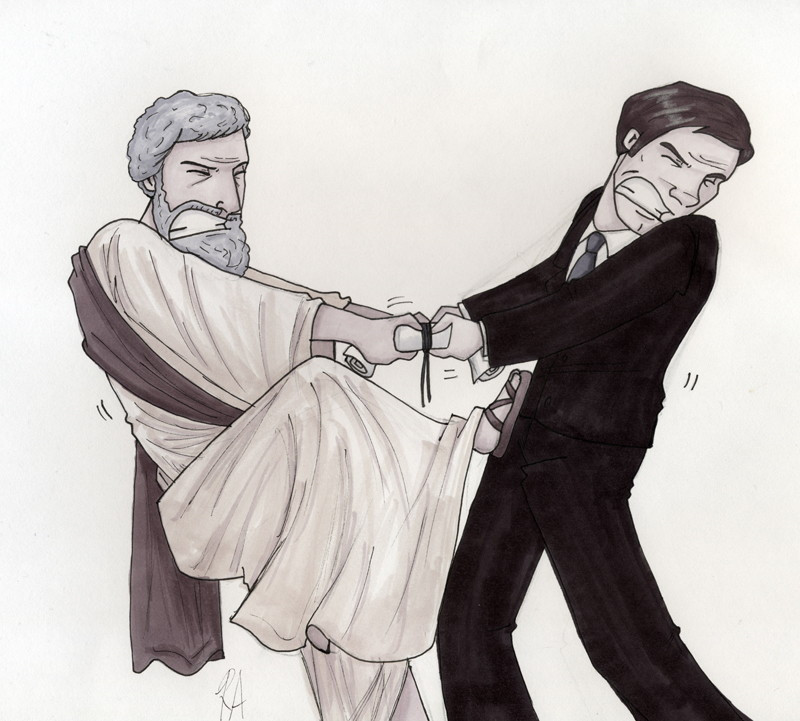

The humanities teach students how to reason in situations wherein the full body of facts is inaccessible. The natural sciences are not particularly helpful in dealing with problems of miscommunication, aggression, inequality and manipulation.

“ Many of life’s most trying situations require one to reason without the luxury of scientific decisiveness

Those problems that fall under human imperfection – problems of emotion, ideals, and judgments – fall to the humanities to interpret and deal with.

Do not be mistaken, though. This is not to say that the humanities, as a discipline, approaches these problems non-objectively or teaches faulty reasoning. Rather, they deal with them as objectively as possible.

Most humanities students are familiar with the principals of logic, analytical consideration of facts and the habit of objective reasoning. Moreover, they are familiar with how to employ these concepts in situations where cold scientific analysis of facts is simply not adequate.

Besides practicality, there is other value in the humanities. Familiarity with the humanities encourages good morals and forces students to consider how to live their lives by studying the actions of others (both historical and fictional).

Without the humanities, we would lose our ability to communicate clearly and eloquently. Not to mention, we would forget the important lessons history has taught us.

“To know a man as a whole being, we must also know his culture,” Plato once said.

Surely then, to lose the humanities would be to lose part of our understanding of humankind.

Chris Hunter is a rhetoric and communications student at the University of Winnipeg. In his spare time he does strange and terrible things with words.

Published in Volume 65, Number 2 of The Uniter (September 9, 2010)