Manitoba’s PCs: The two-pronged party

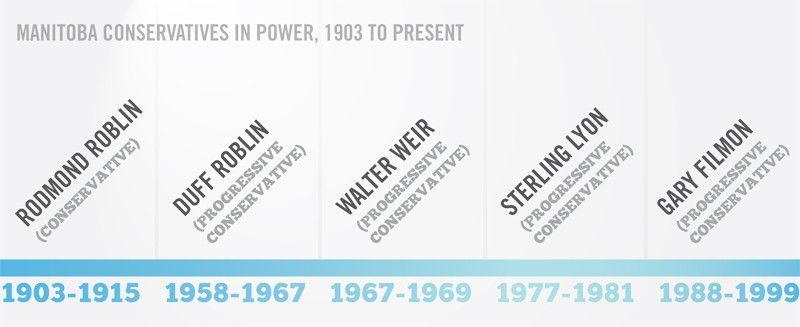

Since the days of Duff Roblin, Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative party has been challenged with uniting two conflicting value systems from two broad regions of support.

Kelly Saunders, a politics professor from Brandon University, affirms the parties support traditionally divides between two demographics.

“The progressive side of the party reflects a more centrist urban Winnipeg, the conservative side has its roots in rural areas,” said Saunders. “The focus of each side tends to be a bit different.”

For every modern PC leader, finding a means of maintaining both sides’ support has been a challenge, adds Saunders.

Jared Wesley, an adjunct politics professor at the University of Manitoba and the University of Alberta, agrees.

“Since the 1960s, the PC party has been challenged to reconcile two competing elements in their parties – the rural conservative wing and the progressive wing,” he said. “The Manitoba party tends to be heavily rural, but in order to get back into government they have to woo urban progressive conservatives.”

For Senator Donald Plett of the federal Conservative party, a rural and urban split should hardly be regarded as a uniquely PC problem.

“I don’t think it’s unique to the PC party that there are different priorities rurally and urbanely,” said Plett. “When we draw a platform these are challenges we face along with other parties.”

Wesley also believes all parties face this problem.

“These are competing factions within every party and are not unique to the PC party,” he said.

Gary Filmon, former PC premier of Manitoba, has always found PC values to be applicable to a wide spectrum of voters.

“I grew up in the North End and there I saw the Conservative party as having values and priorities important to urban dwellers,” he said. “Later, when I was in office, we did well with urban voters.”

However, though values and platforms are constructed to appeal to both rural and urban voters, voters often sway otherwise.

Until 1999, south and north Manitoba were more or less divided among the PC and NDP parties, said Saunders.

“The rule of thumb is that you can draw a diagonal line across the province where everything south is Conservative and everything north is hardcore NDP,” she said. “That dramatically shifted in 1999 when we saw a number of southern ridings going NDP.”

Wesley, however, argues party support has hardly changed since the 1960s.

“People lower on the social economic ladder, people of non-British origin and people in the north tend to vote New Democrat,” he said. “Anyone in the south of the province tends to go conservative. This has not changed much since the 1960s.”

Wesley holds that this divide is so distinct that central ridings are of prime concern in elections.

“The line where it is most competitive is where north Winnipeg meets south,” he said. “Only 14,000 people matter in this election, that’s the 14,000 on that line.”

Plett believes otherwise.

“The media somewhat overplays that (the north-south distinction),” he said. “We (the PC party) have huge contentions in the Pas and Flin Flon.”

“ Since the 1960s, the PC party have been challenged to reconcile two competing elements in their parties – the rural conservative wing and the progressive wing.

Jared Wesley, adjunct politics professor, University of Manitoba and University of Alberta

Plett adds that the north-south distinction has created unfair stereotypes.

“I think it’s unfair for Conservatives to be stereotyped as a party that is not there for the people that are not economically well off,” he said. “For the NDP to say they are the party of the poor people is absolute hogwash.”

Wesley also notes the falsity of these stereotypes.

“The most affluent and educated people tend to vote NDP these days, especially with the Liberal party out,” he said.

Saunders argues that the only thing changing about the parties support is the female vote.

“Voters still tend to be higher income levels,” she said. “However, the gap between men and women seem to be closing and now more women are voting Conservative more than ever.”

Plett dismisses the notion of a solely high-income bracket supporting the party.

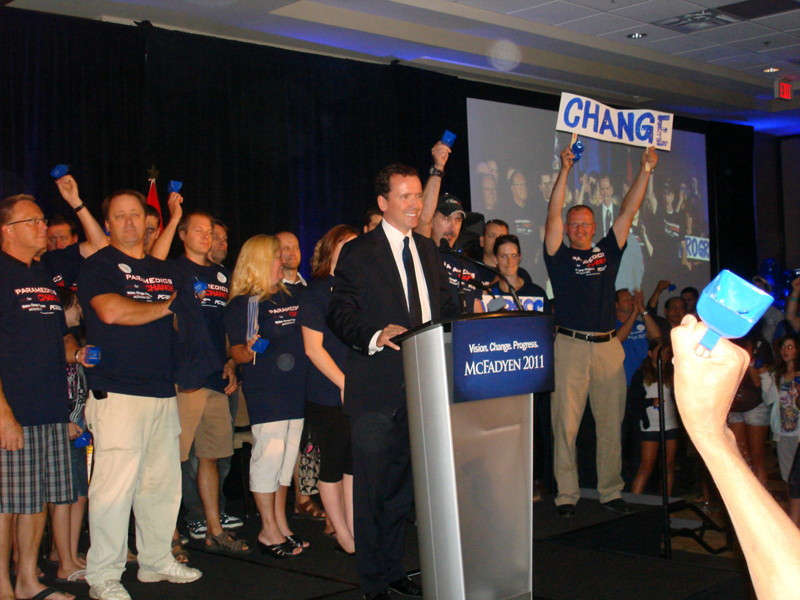

“I would absolutely, entirely dispel that myth,” he said. “We have support from farmers, executives, business owners, school teachers, factory line workers, paramedics – I believe that we have strong support across the entire spectrum.”

Plett argues that making such broad generalizations about demographic support is ineffective and that it is far better to consider smaller groups separately.

“They are a demographic, like unions for example,” he said. “They would be more supportive to the NDP, but that’s not to say their members would be.”

Published in Volume 66, Number 5 of The Uniter (September 29, 2011)