Lost Winnipeg

Out with the old: How the government’s distaste for mixed use zoning damaged our downtown

Old Market Square, the place in the Exchange to go for historically-themed walking tours, free concerts of dubious quality, or some great people watching (“Hipster or Hobo?” is always a fun game), is actually not that old at all. Built in the 1970s on the site of the old Central Fire Hall as a farmer‘s market and green space, the “Old” was thrown in to add some quaint venerability to the place. The original Market Square was a block north, now buried underneath the Public Safety Building and Civic Parkade.

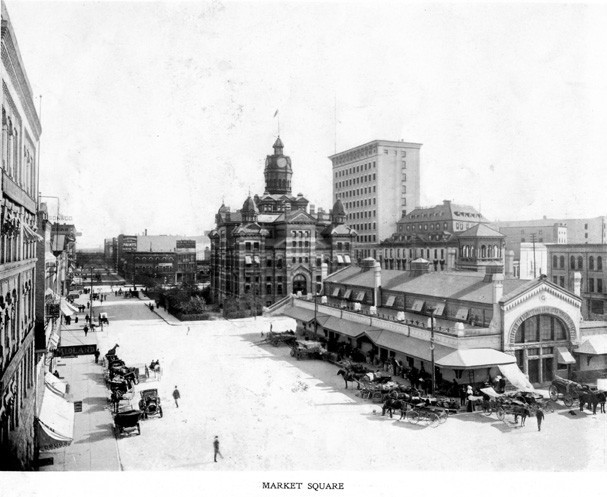

The original Square was laid out on the Ross family estate, and operated as a public market as early as May 1873, months before the City of Winnipeg was incorporated. After incorporation, the market became municipally owned and operated, and a building was constructed so that it could stay open through the winter. Around 1920 this building was renovated into offices for civic employees, but the outdoor market continued to sell produce, flowers, seeds and, in December, Christmas trees.

More than just annuals and blueberries, Market Square was a place for the exchange of ideas. In 1939, a story in the Winnipeg Tribune compared it to London’s Speakers’ Corner, saying that as many as five political and religious meetings would occur simultaneously. The paper also recalls young “junkers” hanging around the Square looking for heroin fixes, and “rub-a-dub” men who descended from the riverbanks, loading docks and flophouses to panhandle in the Square.

“ The new City Hall was cold, insular and underwhelming; a squat little municipal box

Between Main Street and Market Square was City Hall. Built in 1884, the “gingerbread house” seat of municipal government was a cornucopia of Victorian architecture’s eccentricities. In the 1950s, the city government was eager to rebuild City Hall and the neighbourhood around it as a more streamlined and orderly place, and plans for a massive Civic Centre began. To city planners at the time, the neighbourhood embodied everything wrong with cities: Aging, dense, micro-scaled and mixed. The cheap bars and cheaper hotels lured the old men that sat around the Square during the day. At night, kids would come there for movies, booze, late-night Chop Suey, and the city’s jazz scene which centred around Market Square in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Worse than a semblance of mixed-use urbanity and nightlife was car traffic that didn’t move fast enough, and so King and Princess were converted to one-way traffic and streets, and Market Avenue from Princess to Main was eliminated altogether.

City Hall, along with the block north of it that housed more than 100 residents and a dozen businesses, was finally demolished in 1962 for a new council chamber and civic offices. Across King Street, Market Square and another block of residences and businesses made way for the Public Safety Building and Civic Parkade, built in 1965 with an eternally vacant little park thrown in.

Its doors turned inward to a courtyard, the new City Hall was cold, insular and underwhelming; a squat little municipal box. Meanwhile, the Public Safety Building was a misadventure in Brutalist architecture, its design better suited to something built to the scale of a toaster oven.

Gradually, the surrounding blocks joined City Hall and the old Market in the dustbin of Winnipeg history: The Concert Hall and Manitoba Museum took up two blocks east of Main in 1968, completing the Civic Centre complex; and half of Chinatown was lost by the late ‘80s.

With urban renewal now seen purely as a government-led venture, owners of the remaining old buildings north of the Civic Centre simply gave up, waiting for a buy-out when the next megaproject du jour would come along and rescue the neighbourhood from itself.

Buildings sat rotting, or came down for parking lots.

To the left, the demise of the Square, for decades a centre for socialist rallies and the beginning point of the May Day parade, could be seen as another loss of their gathering places. To the right, the Civic Centre was the trumping of property rights and commerce by an increasingly centralized government. But in the early 1960s, the twilight of post-war adulation of everything new and modern, there were few who would argue with these sweeping physical changes.

More than the displacement of countless businesses and residents, or the loss of many architectural gems, the misanthropic Civic Centre eliminated Winnipeg’s own public square, the centre a city’s life throughout 10,000 years of urban history, replacing the neighbourhood with a malignant dead space devoid of a city’s dynamic matter, form, and energy.

Published in Volume 63, Number 30 of The Uniter (August 13, 2009)