What to expect when you’re expecting to be hospitalized

Life on the Borderline

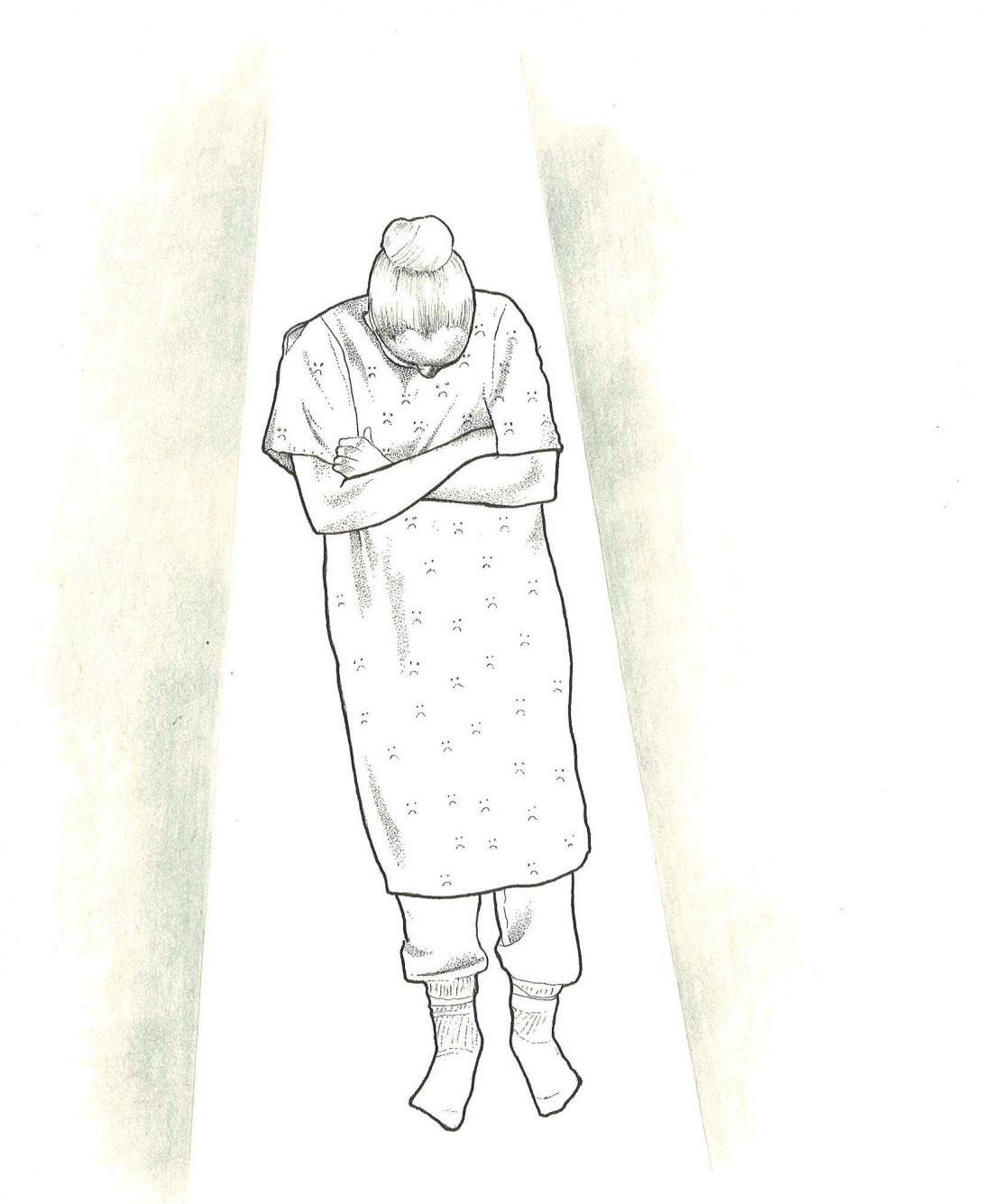

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

The first thing I had to do was surrender all of my belongings, even my clothes.

I was given men’s pyjama pants that didn’t fit, a hospital gown open to the back and disposable shoe guards to wear as slippers. I was shown to my empty, bare room where I stood at the window, watching my partner drive away, feeling more alone than I ever had in my life.

When I asked to be admitted, I didn’t know what to expect other than healing. Being admitted to a psychiatric ward is not like it’s portrayed in the media. There’s no motley bunch of unlikely friends who come together to make great realizations about themselves. In fact, there’s almost no interaction at all.

In the five days I spent admitted, I saw one psychiatrist for 20 minutes two days after admission and a different one two days later for 15 minutes. The only time I got to talk one-on-one with a nurse was when I had a panic attack. But even then, I felt like she was rushing to get back to the desk.

I was given worksheets for a type of self-directed therapy (Cognitive Behaviour Therapy) that I had already determined was not helpful with my counsellor, but was told by the nurse that maybe if I did it again, I would get something different out of it.

I was told by one psychiatrist and a few nurses that they didn’t know why I was there. They said that the three years since I had been traumatized last was long enough for my mental wounds to have healed. Saying that I didn’t want to live anymore earned me the label “attention-seeking,” and I was left to sit in silence, alone in my room and figure out how to make the most of my time away.

Let me be very clear. When someone says they do not want to live anymore, attention must be paid. It is not wrong for someone to seek attention, in this case medical, when they feel their life is in danger. Someone experiencing a heart attack would not typically be labelled as “attention-seeking” for asking for life-saving treatment. The same must be said for someone succumbing to mental illness.

The part of this experience that continues to haunt me is how easy I had it. I was the only white person, despite half the patients being replaced by new ones while I was there. I was told by one man that he felt disconnected from his traditions, alienated in the place where he was being forced to heal in a manner that didn’t make sense to him and wasn’t properly explained to him.

I received care that, although flawed, made sense to me culturally. I had a support system waiting for me at home. I had the resources to purchase a year’s worth of sessions with a clinical psychologist afterwards.

I am overwhelmingly lucky that I was able to heal, despite the way I was treated in the hospital, the place that is supposed to offer the highest level of care available. Far too many are not able to.

Hannah Magnusson is a master’s student in the arts department at Athabasca University. Her research focuses on the intersection of storytelling and advocacy, studying how fostering empathy between different perspectives can build a bridge to understanding and action. She lives on Treaty 1 territory on the shore of Lake Winnipeg.

Published in Volume 75, Number 09 of The Uniter (November 12, 2020)