It’s time for Canada to act like a developed country

Everyone should have access to safe drinking water

In late January, Winnipeg declared its first ever city-wide boil water advisory. Though it turned out to be a false alarm, the whole city was abuzz about it, fearing the possibility of getting E. coli.

Twitter and Facebook were lighting up with photos of bare shelves and people complaining about not being able to shower the next day, even though the advisory really just meant you shouldn’t drink the water without boiling it first.

While the advisory was an inconvenience, it was not even close to what many First Nations communities experience on a daily basis.

Our water boil advisory only lasted a few days, but imagine if it lasted for the months, or even for the years that First Nations communities have had to deal with?

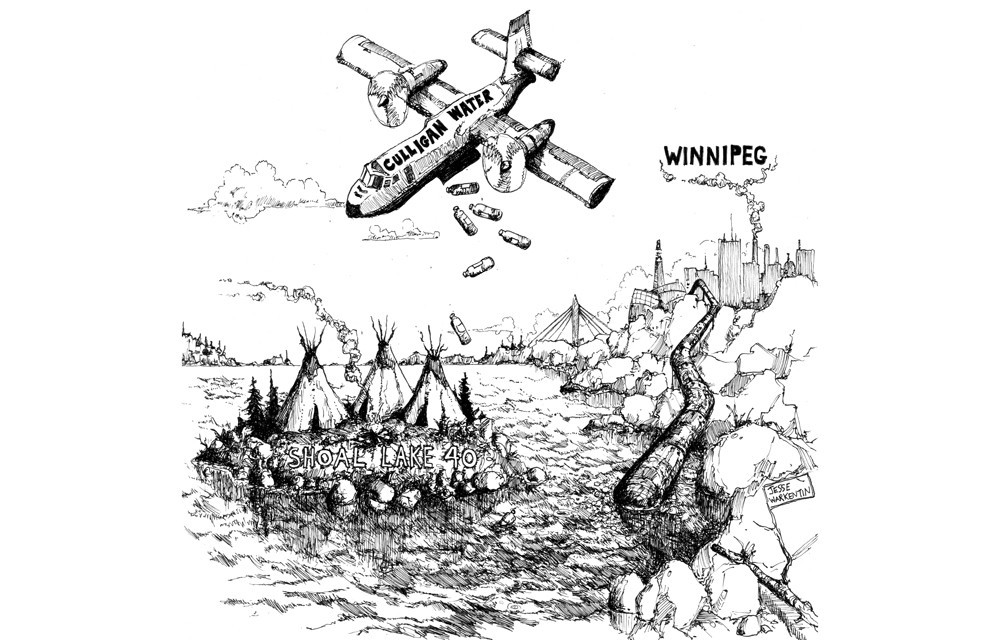

Our city’s water boil advisory - despite being a false alarm - was taken care of right away. Yet some First Nations communities, in particular Shoal Lake, have been under a boil water advisory for about a decade and a half. If our water-boil advisory was still ongoing, I know many of us would be completely outraged at the government for their lack of action. While many First Nations communities have expressed their outrage over their lack of access to safe drinking water, the government has failed to do anything about it.

Last May, James Anaya, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, shed more light on the government’s negligence of First Nations communities. Anaya’s report described how living conditions of First Nations people weren’t up to par with the living conditions of the rest of Canada. While the report did praise Canada’s efforts at improving First Nations economic standing, it made clear that far too many First Nations communities lack access to the basic necessities most of us take for granted.

The UN report - and the subsequent lack of response to it - raises troubling questions.

If the UN quickly realized how bad the living conditions were in many First Nations communities, why has our government done so little to correct it?

Why were Winnipeg’s water problems addressed so quickly, yet some reserves are still waiting decades later?

Why do we say that Canada is a developed country, despite doing little to help many of our people who are living in developing world conditions?

If we want to keep calling ourselves a developed country, we must answer these questions. Being a developed country is about action, not words. It’s time we acted like one.

Patricia Navidad is a first year Rhetoric, Writing and Communications student and travel enthusiast.

Published in Volume 69, Number 21 of The Uniter (February 18, 2015)