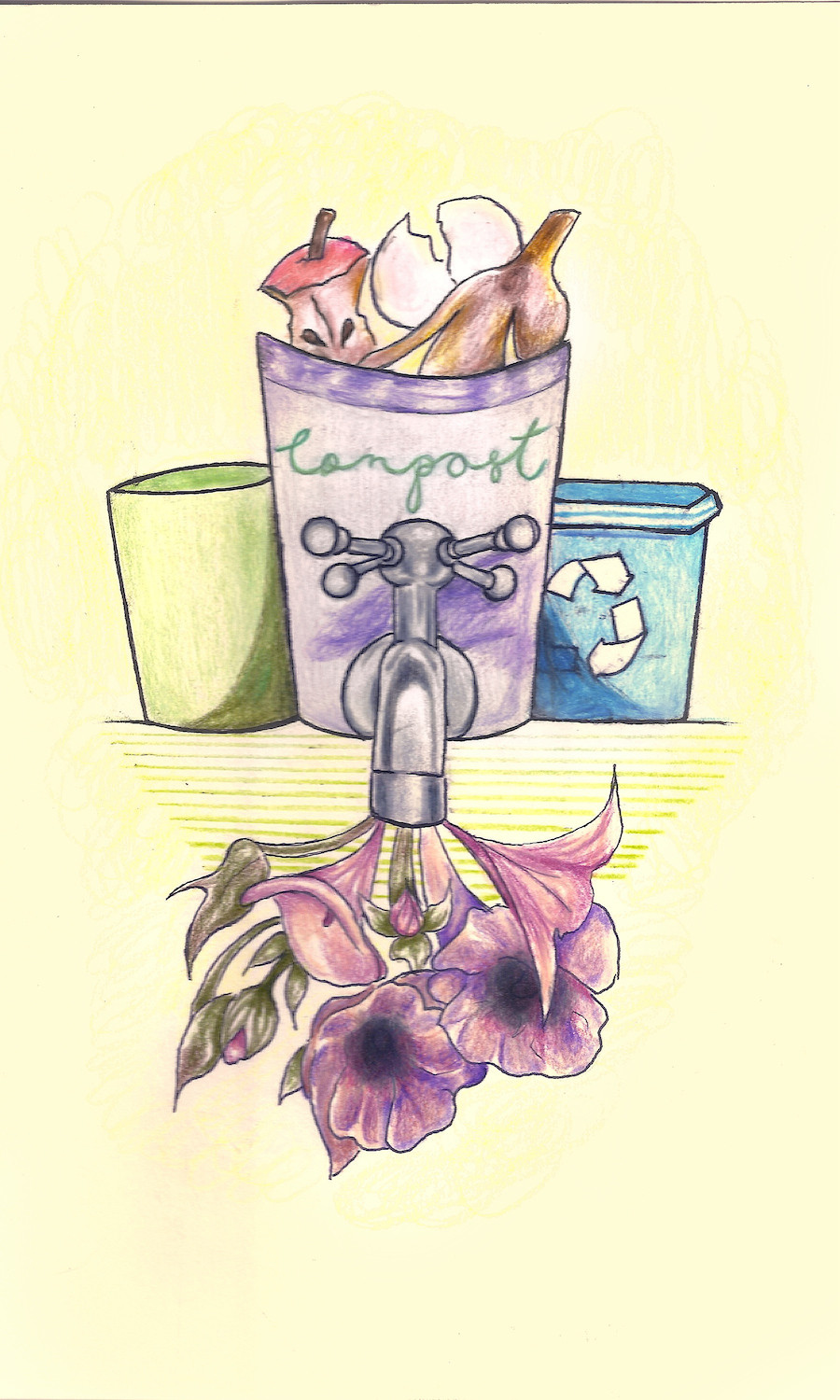

Get with the composting program

The environmental cost of landfilling isn’t worth the short term savings in our pockets

Widespread support for a municipal composting program isn’t as exciting as a debate about whether we should compost at all. But when you talk to people who know their shit – the local compost experts – it’s pretty clear that burying organic waste in a landfill is no longer an option.

“We are quite behind the game,” says Dr. Mario Tenuta, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Applied Soil Ecology at the University of Manitoba. “(Landfilling) organics should have been stopped 10-15 years ago.”

Edmonton began municipal organic collections in 2000, and Brandon began a pilot program in 2010. Even rural Manitoba beat Winnipeg to the compost game: St. Pierre-Jolys and the RM of De Salaberry started composting organics in 2012.

“For years and years we haven’t been treating our earth like we should, and when we buy something a lot of times the environmental costs aren’t included,” says Sylvie Hébert, community composting coordinator at Green Action Centre. “When it comes to composting, we’re actually probably saving money in the end.”

Composting has the potential to reduce two major contributors to greenhouse gases. Methane is released when organic waste breaks down in a landfill, and is 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Nitrous oxide is released by chemical fertilizers and has roughly 300 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide. Applying quality compost to soils can eliminate the need for chemical fertilizers altogether, which is significant when you consider that the Koch Fertilizer Plant alone produces three per cent of Manitoba’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

The City of Winnipeg is gearing up for public consultations on its organic waste strategy, which has three proposed tiers. The first and least expensive tier would collect and compost residential fruit and vegetable scraps, paper towels, and napkins. The second tier would add dairy and meat products, and the third would incorporate pet waste. The costs range from $55 to $100 per household per year, and are currently proposed to be attached to homeowners’ water bills.

“What makes most sense to me is to go minimum tier two,” suggests Dr. Tenuta. “Get a few years underneath your belt, and then beef up the rigour of the program.”

Hébert supports going straight to the third tier.

“I know if you do the pet waste... people might confuse compostable bags with regular bags, so that can have an issue on the final product,” she says. “But personally, I think we should collect all the organic matter.”

We’re in a tight time financially, and there are not many of us who aren’t feeling the effects of it. So it’s understandable that there’s been a flurry of debate surrounding the potential costs that residents will have to cover. But as Hébert notes, “It’s about realizing what is the cost if we don’t do anything, and there’s going to be huge costs if we don’t.”

What’s most intriguing is not people who protest municipal composting programs out of a fear of the cost, but who are genuinely concerned about the environmental considerations of a practice that is often greenwashed to improve public uptake.

Dr. Elaine Ingham, founder of Soil Foodweb Inc. and chief scientist for Rodale Institute from 2011-14, warns against the quality of compost that is produced by many municipal composting facilities.

“When we go to all of the municipal composting places, they are not making compost; they are making reduced waste. And it’s really horrific stuff.” Partly, this is because municipal composting programs usually aim to collect as much organic material as possible. And when people don’t sort their materials properly, it contaminates the organic inputs, making it difficult to produce quality compost.

Dr. Ingham travels internationally, teaching farmers and environmentalists to examine the microbiology present in their compost and soil. A healthy soil food web includes beneficial bacteria and fungi and many other microorganisms, and is one of the best indicators of healthy soil.

“The key to global climate change, to better nutrition in our plants, to human nutrition, and to human health is recognizing that we have destroyed the life in our agricultural soils, and most of the soils that are impacted by human beings. … It’s not going to take billions of dollars to remedy the problems that we have with our soils – erosions, cementation and water quality could be brought back very rapidly if we could just put the proper biology back in the soil.”

Human health is intimately dependent on the health of the planet, and if we continue to exhaust resources at our current levels, there will be no planet to support us in the coming decades. And then it won’t matter whether we had an extra hundred dollars in our pockets or not. Even if we manage to get away with making poor decisions now, we’re simply accumulating debts that future generations will have to pay back.

Let’s stay focused on the real issues at stake here: which of the three options is going to have the biggest impact on climate change and on the life of our soils? The best choices for our environment will inevitably pay us back in good health and in beautiful places to live.

Bowen Smyth is an educator and writer who offers workshops on the soil food web. He is currently contracted by Compost Winnipeg to pick up organic waste from businesses and apartments in the downtown area.

Published in Volume 70, Number 21 of The Uniter (February 25, 2016)