Feeding Diaspora

Embodying resistance: Feminist killjoys at the table

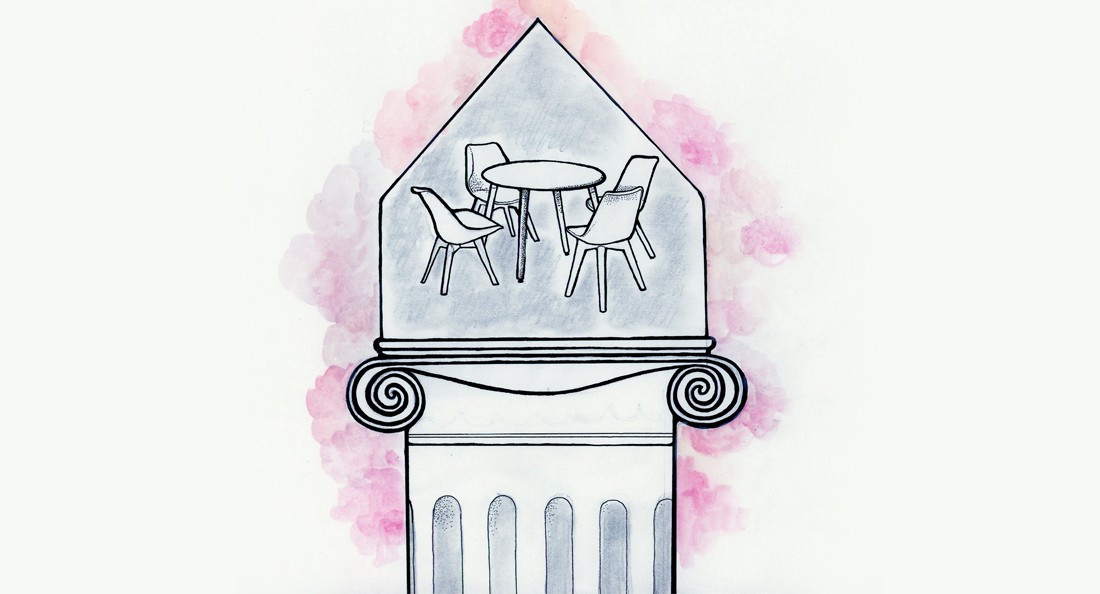

What do you think of when you think of tables? Does the physicality of being seated at a table invoke memories of shared meals? Leisure? Meetings? Work? Your imagined self at a table is always characterized by context: where you are, who you are with and why.

At work or at family dinners, we often find ourselves spending time with people who hold different political views, values, boundaries and communication styles. When faced with a remark that is ignorant or oppressive, feminists are forced to decide how they will respond.

Writer and independent scholar Sara Ahmed coined the term “feminist killjoy” to describe experiences such as this, where a feminist who calls someone in (or out) is seen as disruptive and as killer of joy.

Ahmed’s equation “rolling eyes = feminist pedagogy” describes the looks and eye rolls we get for speaking out or for simply being known to be feminist.

During Ahmed’s Winnipeg lecture on Oct. 3, 2019, and in her most recent book, Living a Feminist Life, she describes the consequences of complaint. By exposing a problem, the killjoy then becomes the problem themselves, she explains.

It is as if people think feminists are oppositional or argumentative for the sake of it. Feminists of colour “do not have to say anything to cause tension,” Ahmed adds, manifesting into racist experiences in both mainstream and feminist/queer spaces.

In institutions, “some, more than others, are at home in these gatherings,” Ahmed says. Being a feminist killjoy is a disorienting feeling, because of the ostracization that is felt as a consequence. Being a queer or trans diasporic killjoy of colour is even more difficult because of the way it amplifies vulnerability and risk, as well as feelings of alienation and displacement.

Because sharing meals is so often a tool of resiliency for diasporic people, it can be devastating to feel misunderstood or misaligned with your family at a dinner. Ahmed describes the way feminists are experienced as disruptive: “another meal ruined” and “another meeting ruined.”

To be a feminist killjoy is to make personal sacrifices for our values when we can afford to. This is necessary if we are to disrupt systems of power. We must do the work around the table, in the spaces we already occupy, behind closed doors.

Diaspora is characterized by a sense of fragmentation and void. However, diaspora is also characterized by gestures of reaching toward: gestures that carve out spaces of belonging, that challenge ourselves and others and that nurture intimacies of hope.

For queer and trans killjoys of colour, to feed diaspora is to learn about ourselves in relation to space and place.

Ahmed leaves me with the hope that to be inquisitive – to transform our pain into questions – is a powerful form of resistance. We embody resistance when we roll our eyes, when we turn to art and writing to find (and create) ourselves, when we sit around difficult tables and decide how to react.

When killjoys gather, the table becomes a different site of resistance – one of nourishment.

Though not without its own conflict, the killjoy gathering is more focused on listening, affirming and uplifting one another. When queer and trans killjoys of colour do this, we create fragments of home and belonging. The table itself is subverted, making way for resiliency, kinship and solidarity.

Christina Hajjar is a first-generation Lebanese-Canadian pisces dyke ghanouj with a splash of tender-loving rose water and a spritz of existential lemon, served on ice, baby. Catch her art, writing and organizing at christinahajjar.com or @garbagebagprincess.

Published in Volume 74, Number 8 of The Uniter (October 31, 2019)