City roots

Getting curious about the canopy

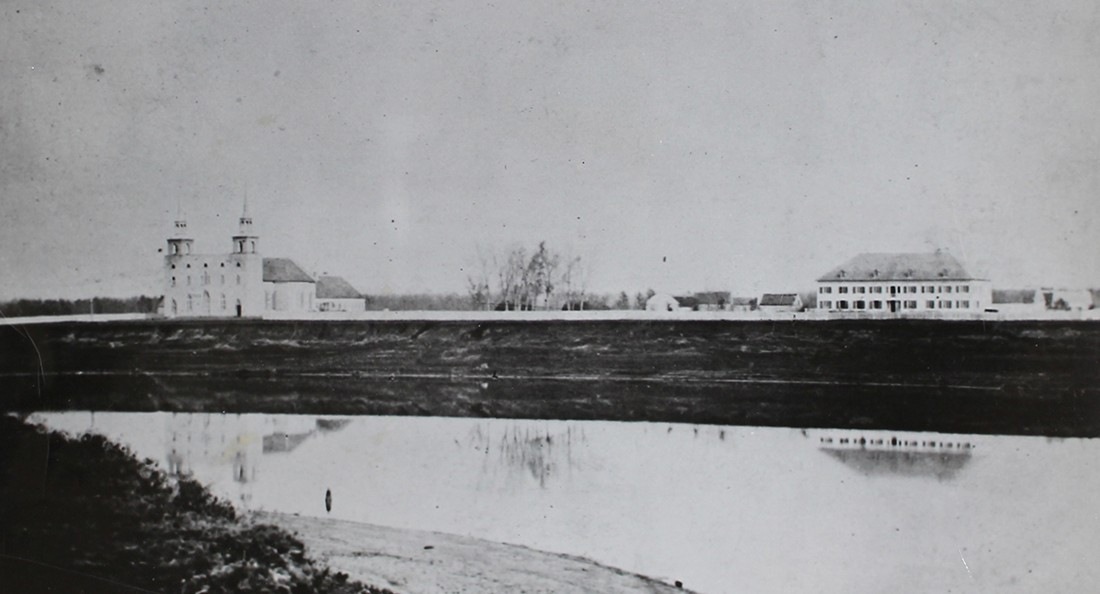

A few years ago, while working as a research assistant, I stumbled upon a photo of an early version of the St. Boniface Cathedral and the Grey Nuns’ convent. My first thought was: Where are all the trees?

I knew this photo was taken in the late 1850s, and it goes without saying that a lot can change in 160 years or so. Still, in my mind, Winnipeg’s riverbanks have always been shady, green spaces, where the trees stretch out over the water, blocking the view of buildings nestled behind them. As I kept digging, I found other historic images from around the same period depicting Upper Fort Garry on the other side of the river to be similarly treeless.

My curiosity was piqued. These early images of Winnipeg looked nothing like the urban forest I knew from flying into or driving through the city. The residential streets, which transform into green tunnels during the summer, are, to me, a defining characteristic of Winnipeg.

What had changed, and why?

Since seeing these images, I have been on the lookout for stories about Winnipeg’s trees. I have learned about the city’s excitement and later disappointment over Arbor Day, the anxieties and desires for city beautification and the explosive tale of the Wolseley Elm.

I am by no means an expert on trees, but I have felt drawn to environmental history during my graduate studies. To me, these are fascinating and exciting stories that I want to share. If history has taught me anything, it is that when you zoom in on anything – even something as specific as the trees of Winnipeg – you will soon find that it is connected to larger histories and bigger questions.

Exploring the history of Winnipeg’s trees tells us something about how people have related to the environment over time. People may view nature as disorderly or sublime, as something to be preserved, modified to suit a purpose or simply exploited for its resources. These are all perspectives that come out of particular worldviews that have changed with time.

To illustrate this, let’s take a little tangent into national parks. Western culture has historically thought of wilderness as a waste of resources and has aimed to claim and control it. But, starting about 200 years ago, governing bodies across the globe increasingly worked to protect pockets of wilderness. This attracted visitors from all over, eager to experience the awe that nature inspires.

The idea was to develop parks that seemed as though they had been “untouched” by humans. Ironically, this was often achieved through the forcible displacement of people who lived in these areas long before the park existed (particularly in parks established before 1980).

Canada’s own Kouchibouguac National Park is just one example of this. The establishment of Kouchibouguac involved the removal of over 1,000 Acadians during the 1970s, along with the attempted removal of all traces of their lives in that space .

The notion that land is in some way spoiled through human presence and must be emptied to be truly “natural” and “wild” is relatively new, but extraordinarily powerful. This idealization of the natural world has been influential enough to motivate governing bodies to forcibly evict families from their homes and their lands.

Winnipeg’s trees can tell us similar stories. This is what I love about history. It encourages us to notice the things we take for granted and to look for their hidden roles in our daily lives.

The trees in our city were planted with the intention to serve a variety of purposes. Their past is interconnected with histories of beauty, morality, class, health, colonization and identity. As I share and explore some of the stories I have learned, I hope to encourage readers to think a little more deeply about our city and its roots.

Kathryn Boschmann is a doctoral student in the history department at Concordia University, whose research focuses on the relationship between religious communities and Indigenous activism in Winnipeg. She was born and raised in Manitoba and has made Winnipeg her home.

Published in Volume 74, Number 4 of The Uniter (September 26, 2019)