Bat Fans

U of W Bat Lab crusading for nocturnal critters

A group of University of Winnipeg (U of W) researchers is vying to save the dwindling bat population and asking for the public’s help.

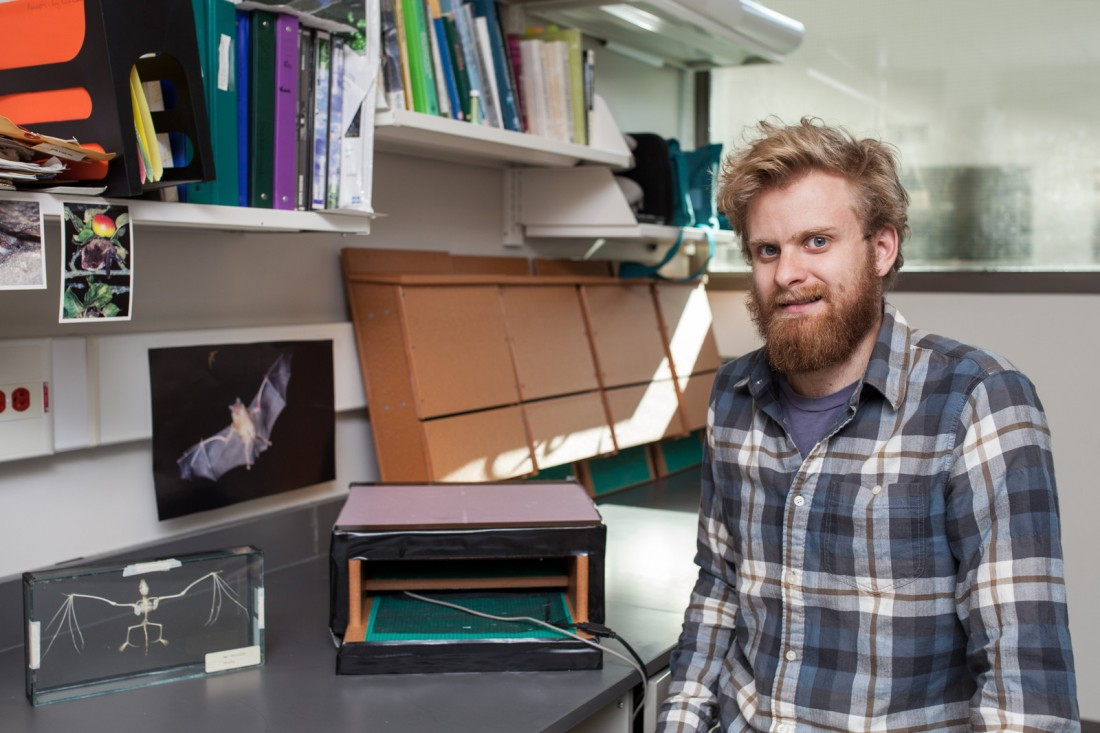

The Bat Lab crew, led by associate professor Dr. Craig Willis, monitors all known bat colonies in Manitoba and Ontario. They’re currently building heat boxes for the little critters in hopes of keeping them warm over the winter, research assistant Kaleigh Norquay says.

The Bat Lab team needs Manitobans’ help identifying bat colonies through the Neighbourhood Bat Watch program. They’re also raising money for the heat boxes through an online crowdsourcing campaign.

Bats can adjust their body temperatures depending on the weather, but pregnant bats or those struggling with White-nose syndrome (WNS) – a fungus that’s endangered the bat population since 2006 – can use the extra hibernation help.

“(WNS) grows on bats as they’re hibernating, into their wing tissue and causes them basically to come out of hibernation much too often,” Norquay explains. “They’re coming up to normal body temperature every two or three days. It’s normal for a hibernator to do that every two or three weeks.”

The Bat Lab crew will start installing the heat boxes near known bat colonies in the winter. So far nine colonies have been reported in Manitoba, with nine more scouted near the Ontario-Manitoba border.

“One of our biggest challenges is finding participants, especially because we’re looking for people who already have bats on their property,” Norquay says.

Many don’t know the positive effects bats can have on their ecosystems either, she adds.

“Here in Canada, all bats are insectivorous… they’re the primary consumer of night-flying insects. So a little brown bat could eat 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in an hour,” she says. “Because we don’t see them and we’re not up at night, it’s really hard for people to understand that link – that they’re actually really important for both agriculture and forestry pests.”

Bats are also largely responsible for pollination and spreading seeds. They provide a bonus service in the southern United States and Mexico.

“Bats are the reason tequila exists. They’re the number one pollinator of the agave. So we should toast them with a margarita,” Norquay says.

One of the Manitoban bat colonies reported to the U of W Bat Lab was Dustin Mymko’s in Cartwright, Man.

Mymko and his wife moved to their Cartwright home two years ago knowing they’d be sharing the property with the bats, who had already lived on the property for 30 years.

“They are on the south side of our house, underneath the clapboard and it’s right next to our bedroom window. So we can hear them leaving at night and then coming back in the morning,” Mymko says.

“We’re not bothered by it, personally. We kind of like them. Sometimes we have a fire in the backyard and we watch them swoop around our heads.”

Mymko’s family was excited to have the U of W researchers come by to visit, he says.

After they temporarily caught some bats, the family was able to see the animals up close for the first time.

“We only seem them as silhouettes that are flying around. We didn’t get to see their teeth and their claws. So having the researchers out was neat to get a closer-up view,” Mymko says.

Published in Volume 70, Number 9 of The Uniter (November 5, 2015)