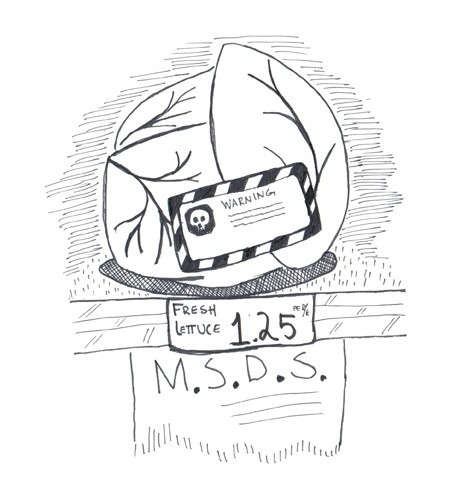

Are you sure you want to eat that?

Determining the source of food contamination is hard, experts say

Food borne illness outbreaks have certainly been hogging the media spotlight as of late.

A salmonella outbreak in a batch of sprouts suspected of causing illnesses in Alberta and possibly Ontario is just the latest in a string of food contamination scares that has Canadians questioning the safety of their food and calling for greater protection.

But food safety professionals say it can be difficult to determine the source of an outbreak.

Salmonella has once again been identified as the likely culprit in a small outbreak of illnesses within Alberta and possibly Ontario. Frequently, cases such as these force Canadians to be suspicious of the food they consume and beg the question of how high a priority food safety really is to those responsible for it.

Distributed by Sunsprout Natural Foods, the sprouts in question tested positive for salmonella during an inspection by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, a fact confirmed by Sunsprout co-owner Don Sinnamon.

“Obviously, we don’t want anyone getting sick from our product. The CFIA is constantly testing us and have launched a full investigation. Still, it’s very hard to link an outbreak to a specific source, especially when there are only a few cases,” he said.

Sinnamon’s sentiments are echoed by CFIA food safety and recall specialist Garfield Balsom.

“We don’t have a direct link to the outbreak situation. An investigation can be quite extensive and complicated. It involves steps like following [people’s] food histories and inspecting the facilities [where the product was produced],” he said.

So the sprouts have gone bad, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they are the offending food source.

Difficulties in determining contaminated sources are not new and neither is the problem of contaminated food. The issue is then raised as to whether the problem is systemic and if there are more effective ways to ensure that the sustenance food that reaches our stomachs is truly safe.

“We need to ask ourselves if we are doing the right things, not simply are we doing things right. I am not sure that we are,” explained Dr. Rick Holley, professor of food microbiology and food safety at the University of Manitoba.

Holley said that while the media only focuses on food safety when there is an outbreak situation, public outcries for more inspection of finished products won’t put a dent in food-borne illness occurrence.

“The key is prevention and education. Food producers don’t want to make people sick. But you need to have a culture of food safety and a food safety system in place so you know that when the finished product reaches the public it is safe. You don’t want to fix a car once it’s on the road – you need to make sure it’s safe to drive in the first place,” he said.

Holley advocates a more streamlined and enlightened education process for food safety professionals across all levels of government. Currently, responsibility is allocated to a food safety workforce of varied backgrounds and disciplines. This means food is either not inspected, or is inspected by different agencies and departments.

“People at the level of food service and production need to understand more than simply the cosmetics of what they are doing. They need to be educated about different risk factors associated with different foods and how that relates to food-borne illness. We need to focus our resources. The government needs to ante up,” he said.

Published in Volume 64, Number 1 of The Uniter (September 3, 2009)