‘An enabler and a life preserver’

For people with eating disorders, Instagram is a double-edged sword

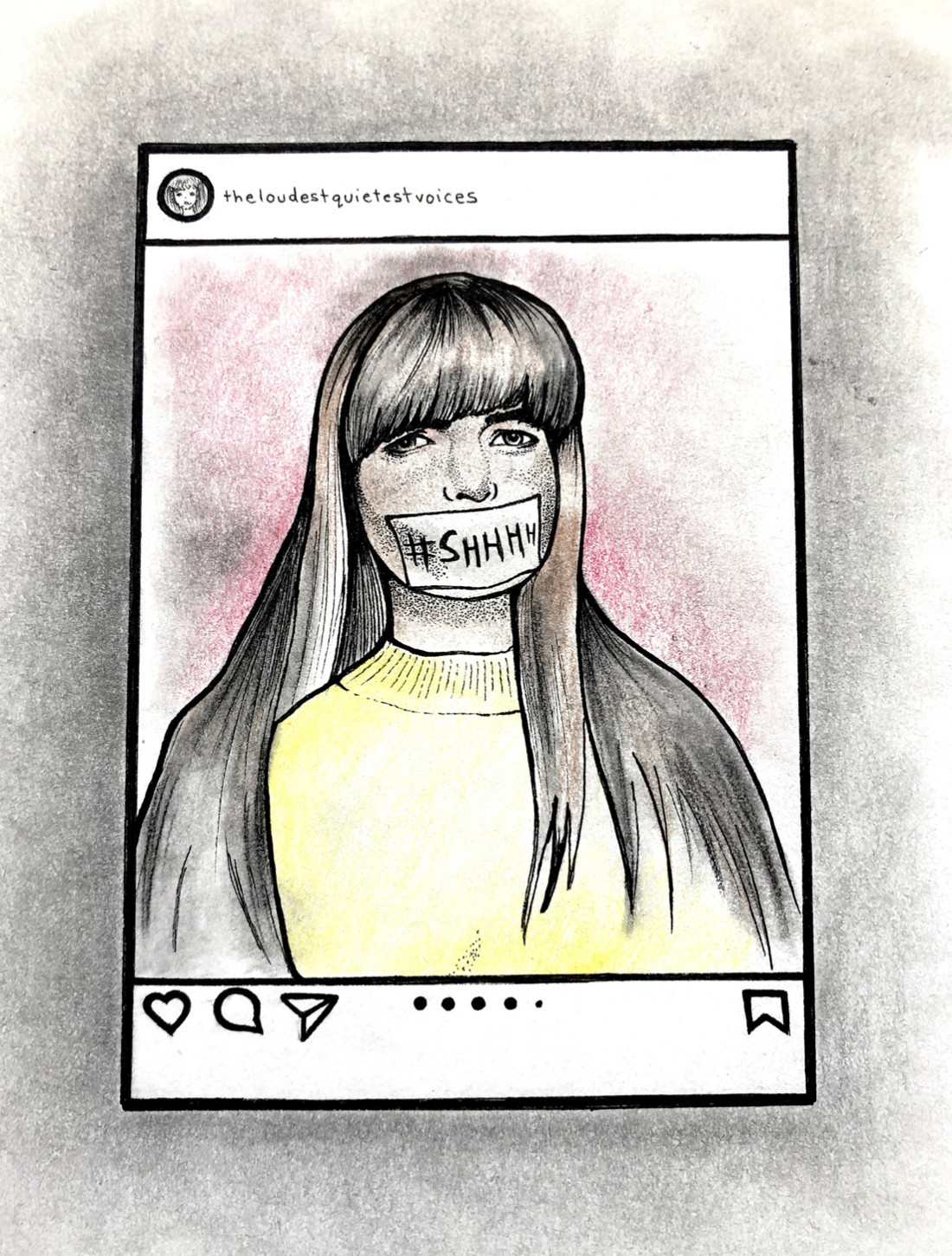

Illustration by Gabrielle Funk

During my third year of college, I remember sitting on the edge of the bed and telling my then-partner I couldn’t eat. I had been living with eating disorders for more than a decade, but this was likely the first time I mentioned them out loud. When he didn’t know how to help me, I took to the internet.

I didn’t seek out a professional counsellor right away. I spent years surrounded by people who recognized my illnesses but didn’t seem to deeply, viscerally understand my experiences. So I blogged about them.

One of my classmates did the same. Reading her story helped me better understand and process my own. Now, I share snippets of my recovery on Instagram, something that’s helped me better connect with people and talk openly in my real life.

However, these same social-media platforms can also exacerbate others’ illnesses. Sites like Instagram, TikTok and Pinterest have repeatedly tried to block posts that could encourage eating disorders. “Discovering, damage-controlling and deleting (pro-anorexia) content has become a rite of passage for web companies,” Ysabel Gerrard writes in a WIRED article.

This is far from a new concept. In an attempt to crack down on misinformation, Instagram temporarily eliminated their “recent” tab from hashtag pages in advance of last year’s presidential election. The platform also adds warnings to posts and stories that mention the coronavirus. Users who click on them are redirected to credible public-health websites.

Search for #AnorexiaRecovery, and Instagram will display a content advisory warning and support resources. Hashtags like #Thinspiration have been blocked entirely. But, as Georgia Tech researchers found, these types of bans didn’t stop people from searching for specific terms. Instead, they used variants.

“‘Thighgap’ became ‘thyghgapp.’ ‘Thinspo’ became ‘thinspooooo,’” a WIRED writer noted in 2016. “Only 17 terms were banned by Instagram, but according to the Georgia Tech researchers, there were 250 variations – many of which promoted even more triggering material.”

As De Elizabeth writes for Glamour, “Banning thinspo content is kind of like playing whack-a-mole – as soon as a site bans a certain hashtag, another pops up in its place.” And that’s not even the most pervasive problem.

“Whether we’re searching for it or not, our feeds are filled with images of “perfect” bodies that, at the very least, can contribute to negative self-esteem, and at worst serve as triggers for those of us living under the shadow of an eating disorder.”

The internet was “an unmistakable accomplice” in De Elizabeth’s “destructive behaviour.” However, it was also a source of hope.

“This is what makes the Internet so complicated when you have an eating disorder – it’s an enabler and a life preserver. LiveJournal fed my dangerous appetite for thinness. But it’s also where I finally found my safe haven, when not even my closest friends knew what I was going through.”

It’s easy to say people with eating disorders should avoid social media entirely, but that’s both irresponsible and impossible. It’s also impossible to block or include a warning for every potential search term relating to eating disorders. The warnings that already exist are problematic themselves, because people seeking help may feel chastised or discouraged when searching for specific terms.

There’s no quick fix for the double-edged sword that is Instagram and the internet as a whole. For now, I’m just grateful for the solace both have brought me and so many people who might otherwise struggle and recover in silence.

Danielle Doiron is a writer, editor and marketer who splits her time between Winnipeg and Philadelphia. She’s spending the pandemic reading, practising yoga and cursing out the governments in both cities she calls home.

Published in Volume 75, Number 17 of The Uniter (February 4, 2021)