Lost Winnipeg

South Point Douglas at a crossroads

Do you love learning about our city’s past as much as we do? As part of a four part summer series, Robert Galston, author of local blog The Rise and Sprawl, will examine neighbourhoods’ transitions over the past century, up until the most recent 2006 Census. This month he takes a look at South Point Douglas.

South Point Douglas, that narrow peninsular neighborhood east of Main Street and south of the CP Railway, experienced a 35 per cent population increase between 2001 and 2006, the 2006 Census revealed. And while that might sound impressive in a city that had an overall increase of just over two per cent in the same period, the boom only brought South Point Douglas’ population to 230, up from 170 persons.

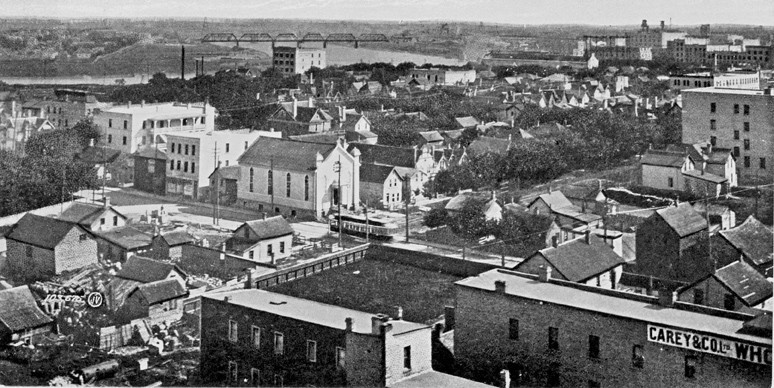

Ninety-five years ago, more than 230 people could have lived on any one of short streets that makes up the neighborhood’s jumbled grid: Martha, Gomez, Duncan, Curtis, Mordaunt. Information from the 1911 Census shows a South Point Douglas packed with residents at the pinnacle of Winnipeg’s dramatic period of growth, when the city’s population grew by nearly 100,000 people between 1901 and 1911. Most of these residents in South Point Douglas were listed as “lodgers” or “roomers” in a family’s house. Some households had as few as one or two, but others had many more, like a young married couple that had 27 roomers living with them in their house on Lily Street. The overwhelming majority of these people were single persons in their 20s, indicative of how much of an economic vortex the city was at the time. For the new arrivals, South Point Douglas would have seemed suitable for its cheap rents and proximity to jobs in the nearby business district.

“ While it has at times been fashionable among civic leaders to talk of South Point Douglas as a “hidden jewel” that oozes “potential,” the restrictive industrial zoning persists today.

The neighborhood of 1911 was as complex as it was dense. The opulent Royal Alexandra Hotel - into which the fictional Sandor Hunyadi from the novel Under the Robs of Death would peer as he passed by - loomed over Higgins and Main not far from the sagging booze cans and pool rooms on Henry Avenue. The Jewish merchants that lived on Lily and Argyle Streets - some prosperous enough to have a maid in their employ - were not far from the “hobo jungle” that had lined the banks of the Red River since the late 19th century (and continues to today).

As the Second World War ended, South Point Douglas was on the wane. If the CP Railway cut the semi-rural enclave of Point Douglas in half in the 1880s, the Disraeli freeway quartered the densely cosmopolitan neighbourhood in the 1960s, displacing hundreds of residents and numerous businesses. Rosh Pina Synagogue at the corner of Henry and Martha followed its congregation to West Kildonan in the late 1950s, and the Royal Alexandra was demolished in 1971. Whatever vestiges were left of a residential neighborhood survived through grandfather clauses, since city planners had by 1966 blanketed it entirely in industrial zoning.

While it has at times been fashionable among civic leaders to talk of South Point Douglas as a “hidden jewel” that oozes “potential,” the restrictive industrial zoning persists today. So while scrap yards, self-storage warehouses and tow trucks are perfectly acceptable, bakeries, bistros and apartments are not.

A still greater impediment looms: the construction of a new Louise Bridge, to be built in 2012 - exactly two centuries after the Selkirk Settlers first arrived at Point Douglas. The city says that it will be a twinned bridge, effectively increasing traffic on Higgins Avenue, already an obnoxious truck route. While the industrial zoning is sure to be amended by the forthcoming Secondary Plan for South Point Douglas, any positive effort of this would be cancelled out by Higgins Avenue turned into even more of an at-grade freeway.

As it was in 1911, South Point Douglas can be dense and complex. In spite of near-paranoid and vague concerns about gentrification, South Point Douglas is able to offer luxury condominiums with the finest skyline views in the city while still offering social services and housing for the city’s poor. It can be a place that is attractive to young people and those new to the city with cheap rents and close proximity to the Exchange District (and for hipsters desperate for authentic dive bars, it would be hard to top the King’s Hotel on Higgins).

South Point Douglas cannot do any of this successfully while also serving as the mighty Atlas that bears every northeast Winnipeg commuter on both the Disraeli Freeway and a busier, less inviting Higgins Avenue. The city must choose if it wants South Point Douglas to be able to return as a strongly-populated and valuable neighborhood, or if it wishes for it to continue disappearing into the past.

Published in Volume 63, Number 27 of The Uniter (May 20, 2009)