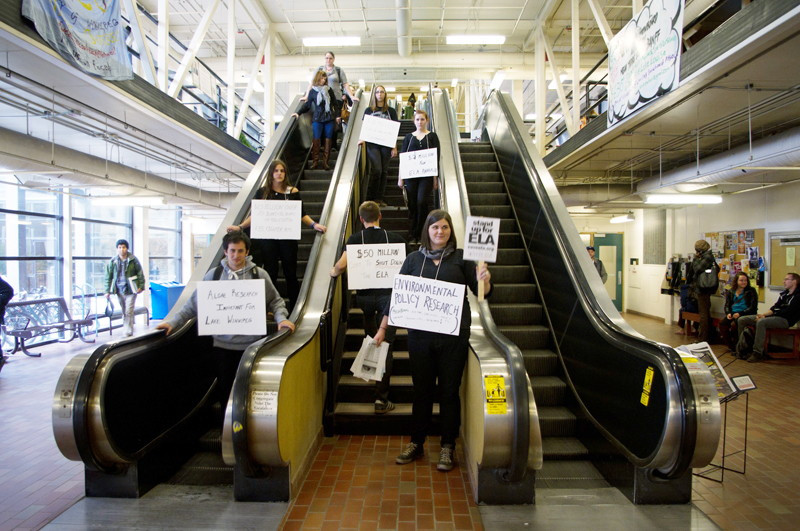

Scientists protest funding cuts to Experimental Lakes Area

Researcher calls Harper government’s approach to science ‘disgusting’

Canada’s environment is taking a backseat to the pursuit of economic prosperity built around the country’s tar sands, a founding director of the Experimental Lakes Area says.

In an interview with The Uniter, Dr. David Schindler, who helped establish the ELA in Northwestern Ontario in the 1960s, said the Conservative government’s proposed closure of the area in March 2013 shows how little Canada’s politicians know about science.

“The whole approach to science of the Harper government is a house of cards, it is disgusting,” said Schindler, who has become one of the world’s leading limnology experts through his work at the ELA.

“They are stripping every scientific program they can to protect the oil sands. They are waiting so industry can get a foothold,” he said. “They view environment as secondary as they worship theirs gods of money and the economy.”

Limnology is the study of inland water systems.

Consisting of 58 lakes and their drainage basins, the ELA has delivered important research about the effects of industrial pollutants, acid rain, aquaculture and algal blooms in watersheds.

In May, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans abruptly cut the facility’s annual $2 million budget, meaning research will end in March 2013 if no new operator is found.

In July, some 2,000 scientists marched to Parliament Hill, protesting the Conservatives’ dismantling of scientific policy. Four of the ELA’s former regional directors, from the 1970s to the mid-1990s, have written Prime Minister Stephen Harper to reverse the decision.

The ELA is currently being used to study the effect of nano-silver, an antimicrobial agent found in laundry detergents, on the watershed.

“There is no other place on earth to add ... major chemicals to a whole ecosystem,” Schindler said. “There is no other place without competing stressors. Other places are an order of magnitude less in scale.”

The Coalition to Save the ELA has gathered more than 24,000 signatures protesting the funding cuts, and has been campaigning to have the ELA remain a public facility.

The closure is the “flagship issue” for confronting the governments anti-science and anti-environment agenda, said coalition director Diane Orihel.

“We are losing the most powerful tool for studying the effects of the tar sands on water, and climate change on watersheds,” she said.

“I’ve tried really hard to keep believing in democracy, but this process is harming that hope. The Conservative government is not listening to science or the people.”

David Gillis, the DFO’s director-general of Ecosystems and Ocean Science, said he is not aware of a comparable research facility in North America.

While creating sustainable aquatic ecosystems is a strategic priority of the department, the ELA has been deemed expendable within the mandate of the government, he said.

The bulk of the department’s mandate is built around commercial fisheries, he noted.

“Ecosystem level research and whole lake manipulation experiments are no longer a priority,” Gillis said.

The DFO has always had a problematic oversight relationship with the ELA because of the department’s priority on commercial fish stocks, Schindler said.

He added that the ELA should have been part of the Department of the Environment from its inception.

Jean-Marc Prevost, spokesperson for provincial Conservation Minister Gord Mackintosh, said the province wants to see the ELA remain publically owned and operated.

Conservative MP Joyce Bateman’s office did not respond by press time.

Published in Volume 67, Number 7 of The Uniter (October 17, 2012)