Memory and looking back

Canadian cartoonist Seth reflects on his work and what makes comics art

He is largely regarded as one of the best and most innovative cartoonists at work today, and he goes by one name only: Seth.

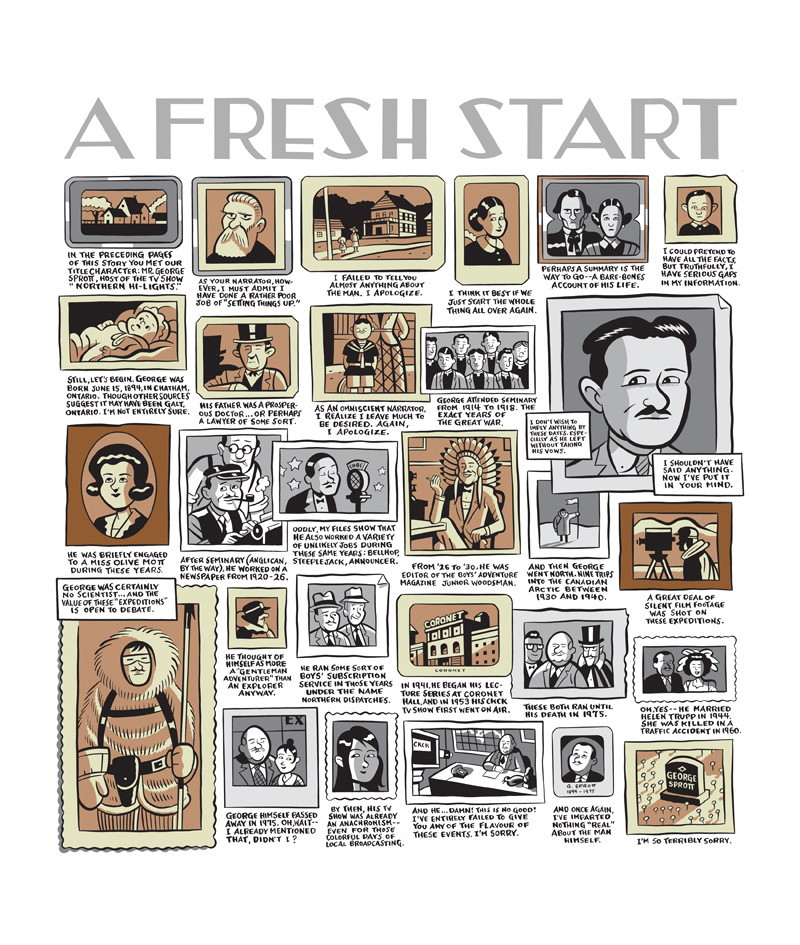

Known to his mother as Gregory Gallant, Seth has several volumes of his own work and has also edited an anthology of Doug Wright cartoons called Doug Wright: Canada’s Master Cartoonist. His most recent original work is George Sprott: 1894-1975.

The cartoonist, who lives in Guelph, Ont., was at the University of Winnipeg on Tuesday, Oct. 20 to give a lecture at the University of Winnipeg.

Seth has dedicated his life to the medium of cartoons, comics and graphic novels. He’s as much an artist as he is a comic historian and collector.

“The funny thing about collecting is that it has almost been indivisible from comic books and that I think has a lot to do with the fact that you had to collect things. Especially as a cartoonist, you had to collect things, if you wanted to discover the origins of your own medium,” the 47-year-old said during a wide-ranging interview at the Inn at the Forks, a few hours after his appearance at the U of W.

When Seth was coming into his own artistic practice and digging deep into the history of comics, he was forced to become an authority on comics as he dug a niche into the comic world.

“To find the history of your medium, there might have been only one or two reference books. And I know now they are full of inaccuracies. It meant comic book shops and second-hand bookstores,” he said.

Seth is turning his wealth of personal knowledge into a more solidified record of comics and cartooning. He is partially laying down a history of comics, as seen in his history of Doug Wright.

“I like the idea of bringing these things back into the world in concrete form. I like the idea of artists of the past getting their dues now. I have a real respect in the artists that came before me and a real interest in what they did.”

If there is anyone left in the world that doesn’t recognize comics as a legitimate art form, Seth gives an excellent defense. As comics have been celebrated in film, in the university and by literary and art critics, it’s hard to let them slide by as an inconsequential medium.

“I began to believe comics were art when I began to see they could really talk about the human condition,” he said.

Seth’s criteria are a result of the relatively recent development of the language used to discuss comics.

“I think a lot of other art forms have stopped worrying about whether the works are meaningful or whether they talk about human life. But comics are really behind. The best artworks really try to tell you what it feels like for that particular person in the world. It’s a limited definition, but when I see that in comics it’s proof that they can be art.”

Seth’s latest book, George Sprott, tells the story of the titular character in the final moments of his life. The book is full of his memories, his looking back and taking stock of his life. It’s a sad book, and George isn’t the most likeable character, either. The story is told in a series of short, disconnected episodes that build to a robust character profile of George.

“ I’m drawn to write about sadness. I’m so interested in the past, it always comes out as the sadness that is connected to the passing of time.

Seth, cartoonist

“George Sprott is really about fragmentation. At every stage I tried to make things more fragmented, so it was really up to the reader to recognize gaps and fill them in themselves. I wanted the reader to make their own decision about what they thought of George,” Seth said.

Seth himself is a reflective person and many of his books are about the process of remembering. The work is generally sad, as characters watch the past slip away from them.

“I’m drawn to write about sadness. I’m so interested in the past, it always comes out as the sadness that is connected to the passing of time. If I was more interested in human relationships it would be the sadness of loneliness. Sadness and loneliness are very distinct,” he said.

“A lot of my work is basically analogy. I feel human life has a sad basis, not that it is inherently sad, but it feels sad. The minute I am away from other people I am sad. The only thing that keeps me from being sad is the distraction of interacting with others,” said Seth.

For Seth, recollecting the past, and the sadness of remembering a life gone by, is very distinct from nostalgia. He said that nostalgia is often a derogatory term, used to label anything with content about the past.

“I don’t like the word nostalgia,” he said. “I’m trying to be aware of looking back - a character like George is actually not reflective enough to know why he is looking back.”

Seth quotes artist Thoreau McDonald on the subject: “As you get older, the world is not your own.”

Published in Volume 64, Number 9 of The Uniter (October 29, 2009)